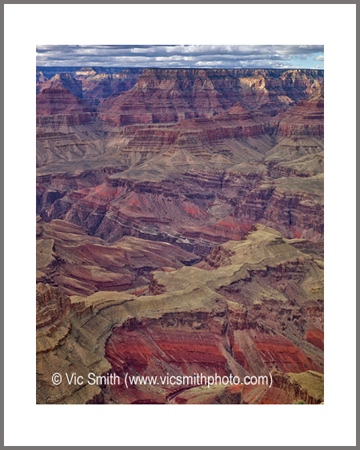

The Grand Canyon must be seen to be believed. To most, that is an “oh, my God” moment. It isn’t the longest, deepest or wildest canyon, coming in at #4 on some lists, but it’s size, complexity and grandeur justify its name. It likely dates from about 5 million years ago, old by human standards, but barely a tick on the scale of the earth’s history. During that tick our Colorado River has made it a slice 277 river miles long, from one quarter to 18 miles wide. It has 167 named rapids and about 225 side canyons. Its southern rim is about 1373 miles long and its northern rim is about 1384 miles long. It cuts into seven named plateaus or platforms. Its maximum depth is 6,000 ft. It’s river drops 2,000 ft in elevation as it flows through it. Harvey Butchart found 12,000 miles of hikeable paths in it between Lee’s Ferry and Pearce Ferry. Its layer cake structure shows scores of landscapes, dunes, rivers, oceans, settled into a low interior basin over 1.8 billion years and then raised over 7,000 ft to its current elevation. It has been land on the move. Its river has carved deep and wide, producing many textures and colors, angles, towers, slopes, canyons and platforms. It is a place of magnificent overload.

Native peoples were the first to see, feel and hear it, to stand on its edge and to walk its center, starting some 13,000 years ago. It was Piapaxa ‘uipi (Big River Canyon) to the southern Paiute, Öngtupka (Salt Canyon) to the Hopi, Chic-a-mi-mi Hackataia to the Havasupai, Tsékooh Hatsoh (Big Space Canyon) to the Navajo, or the work of Pack-i-tha-a-wi to the Hualapai, long before it was a “barrier which nature had fixed” to the Spanish Garces (1776), the Big Cañon of the Colorado to Ives or the Great Unknown to Powell (1895).

Ancestral Puebloans, Southern Paiutes, Hualapai and Havasupai lived, farmed, collected plants, hunted and still recognize culturally human artifacts and natural elements along the banks of the Colorado River. The Hopi people connect their origin story to the Sipapuni, where they climbed up a reed into the fourth world near the confluence of the Colorado and the Little Colorado Rivers. The Zuni people arose from Chimik’yana’kya, near Ribbon Falls. The Canyon and its river have remained sacred to these peoples and their descendants, drawing them back to celebrate their origins.

My experience with the canyon dates from my youth, 1958. A family vacation put us on the south rim, my brother and I sitting near the edge and father pointing his new Voigtländer camera (a unit that I still use) into the depths. ñon. This story and the images I share are a part of the legacy.

I’ve found ways to continue this family legacy, on the rims, on the interior trails, and on the plateaus that bound the Canyon. This story and the images I share are a part of this legacy.

Clarence Dutton, an early geological explorer of the Colorado Plateau and the father of “The Grand Staircase”, described the Canyon this way:

“Whenever we reach the Grand Cañon in the Kaibab it bursts upon the vision in a moment. Seldom is any warning given that we are near the brink. At the Toroweap it is quite otherwise. There we are notified that we are near it a day before we reach it. As the final march to that portion of the chasm is made the scene gradually develops, growing by insensible degrees more grand until at last we stand upon the brink of the inner gorge, where all is before us. In the Kaibab the forest reaches to the sharp edge of the cliff and the pine trees shed their cones into the fathomless depths below.” (Clarence Dutton, 1882)

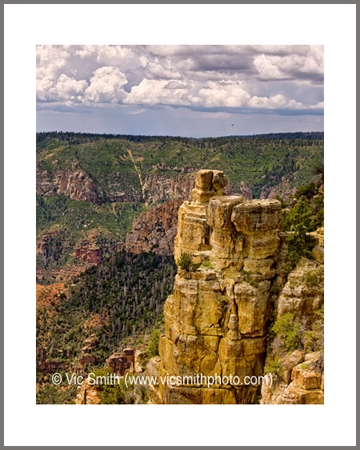

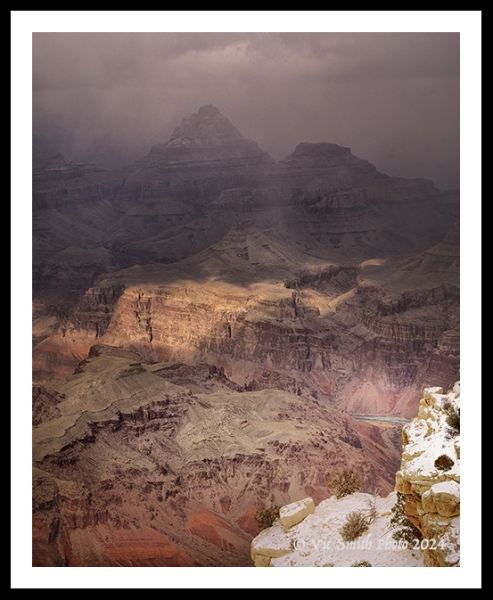

Let’s go to the Canyon. First, join me as we drive along East Rim Drive, on Dutton’s “Kaibab”. We will park along an unpaved fire road, load up our gear and walk to a trailhead, about a half-mile away along the paved road, surrounded by forest. The trailhead is unmarked, recognizable mostly to acolytes actively seeking it. Heading slightly down through low pines and oak, we step down over rock steps, around corners, on red dirt. We can see patches of sky above us through the trees. Then the sky appears ahead of us, down to a rock edge some distance away. The trees stop. We are looking down into the chasm that is Grand, the Grand Canyon.

The edge has arrived suddenly, as Dutton predicted it would.

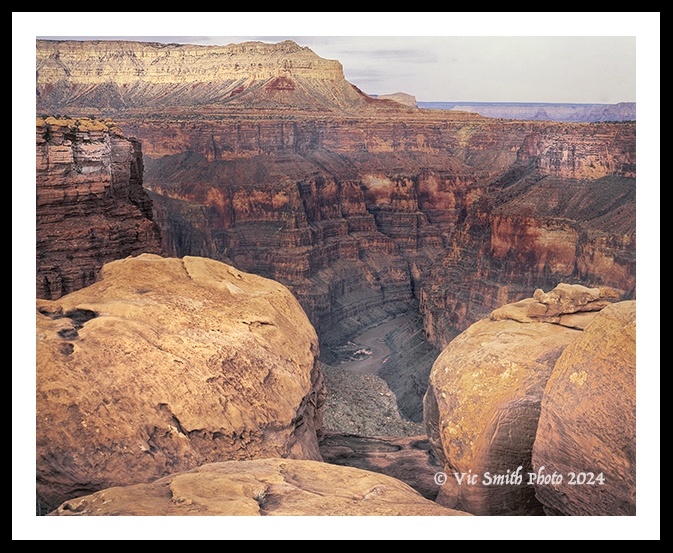

Now join me as we drive a 61 mile dirt road toward the North Rim’s Toroweap. It is lined with sharp rocks, washboardy and dusty. There are a few trees, mainly accents, but mostly low shrubs that spread across dark volcanic bluffs. In the distance we can see peaks, cliffs and some narrow mesas. The land is open and the sky is big. As the end of the road we reach a broad platform with shallow indentations, water pockets. Out there is another part of the Canyon, its chasm beckoning us to approach.

Regardless of how I have approached it, I’ve been stunned by the seemingly infinite space and bounding earth of the Canyon, two pieces, one whole, like standing on the edge between ocean and earth.

“I gazing at the boundaries of granite and spray,

the established sea-marks,

felt behind me

Mountain and plain, the immense breadth of the continent,

before me the

mass and doubled stretch of water”

(Robinson Jeffers, Continents End)

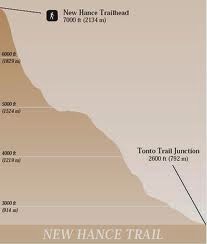

Tipping off from the Kaibab, our way down will be the New Hance Trail, an unmarked, unmaintained route seemingly straight down. The guidebooks are cautious about it and seem to say “use it if you must”. It’s a trail for those in a hurry to get down. It the quickest drop of all the south rim trails, dropping 4,500 ft in just under 7 miles. On the way our feet and lands touch ancient lands and their relics of life, smooth, rough, strong or crumbly. It’s a individual struggle to prove yourself by surviving all the way to the bottom.

The trail was intended for mules, built by “Captain” John Hance to work his asbestos mine on the side of the river and later to take tourists to the bottom. It takes our boots down through boulders and crumbled shale, across steep faces with ball-bearing pebbles under foot and then forces us to slide down limestone faces into the aptly named Red Canyon before boulder-hopping to respite in the dunes of Hance Rapids.

Looking back up to the start, I sink into my own reverie. It seems like I’ve been in a fight. After hours of slipping, sliding and stumbling, the end feels, finally, like something magic has happened: I made it. It feels like I finally landed one good punch, maybe a perfect right cross. The soft dunes and the roar of the river across Hance Rapids are rewards for the challenges endured. They refresh before we move on, toward a return to the rest of what’s dear.

At Toroweap the rewards are different, the result of having successfully negotiated the long, challenging dirt entrance path.

The bottom, the river, is 3,000 ft below us, not directly accessible. If we’re lucky, we’ll see a boat or two bobbing down the river, after 175 miles of transit. We are on top, imagining their lengthy ride, and wondering if they can see us, the mighty rim ants, as we stare down at them. We can only imagine the fight they’ve enjoyed to get to this point in their journey.

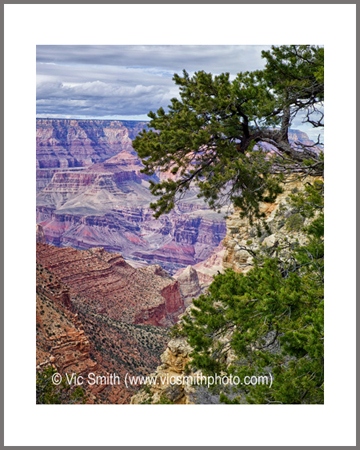

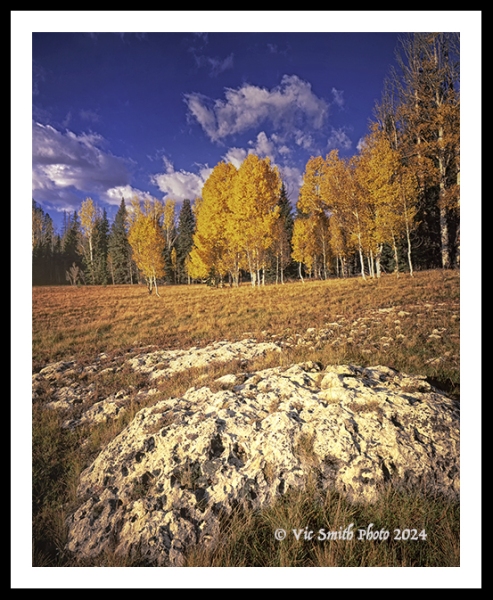

The Canyon is best known for space, steepness and struggle. But it isn’t just about big and deep. It is also about adjacencies, lands filled with little victories, with tall trees, with scrubby plants and tough critters hanging tenaciously to hard rocks in hard climates and wandering through ancient forests, and with little pockets of water retained as long as possible. It is about fires and wind that sweep through and clear the way for new life. It is about people returning to their sacred roots, about people trying to scratch out a living from the hardscrabble earth, about colorful folks telling tales that bemuse visitors and about buildings sculpted from the earth on which they sit, looking down stunning side canyons. It is a place big enough for everyone to find their remembrances and their own reasons to return.

I admit to feeling presumptuous for this brief piece and the images that follow. There are many vantages from which to appreciate the Grand Canyon, not all precipitous. I am sharing some of them in gallery below. There are more that I haven’t seen or have seen and haven’t adequately recorded. There are many people who know more, have seen more and have captured more in images, words and traditions. I heartily recommend that you visit them if you want to see a more complete story. Their vision has created footsteps for us to follow.

Please enjoy these words and images as a first offering:

Please enjoy this place and these images. Come back and read the rest. You’ll like it.