Today is groundhog day in my land of the hunkered. A friend just brought holiday cookies. Did we sit and catch up? No. We exchanged our gifts and bumped fists. She went on. I returned to my tasks. I’ve done many of the home projects that I’m capable of performing. There’s no snow to test my projects. I’ve talked with my Covid-cautious children and friends. I’ve organized until my mind is glazed and piles are moving on their own. I find myself doing the same things over and over, hoping the outcomes will improve.

Then I see two books winking at me: My First Summer In The Sierra by John Muir, and Beyond the Hundredth Meridian by Wallace Stegner. Both could get me out of my cave and where I want to be: the American West. Muir’s stories are soul-filling paeans, to the majesty, power, beauty of the Sierra Nevada, its land, water, trees, plants, and clouds, searches for “pure wildness”. Stegner gives me John Wesley Powell, his western explorations, his respect for native peoples, and his sensible husbanding of water in this arid “Plateau Province” (west of the hundredth meridian).

A glimmer of purpose arises. Amid the books, 70,000 image files, piles of slides and negatives, and story snippets I’ve started but not finished, I discover a little project to engage my memories and my imagination, from a past trip into one of my magical places: southern Utah. Maybe I can ride those old images to a new space. Maybe I can escape for a bit.

The trip was in 2010. I was invited by Rick Knepp, a friend and early photographic mentor, to assist in a field seminar. Thirteen of Rick’s devoted light-chasers would meet us outside Bryce Canyon National Park and then travel the Golden Circle, the magnificent landscapes of Bryce Canyon and Capital Reef National Parks and the land between. He would teach photography. I would give the geological context for what we would see (a heady goal given that I had just started guiding, as a Docent at the Museum of Northern Arizona).

I went with a personal history of the area. Back in the 1950’s my parents took us on a kind of grand circle tour of the southwest: New Mexico, Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce Canyon, and more. My Dad used his Voigtländer camera and Kodachrome film to capture the memories. I have a print of one scene hanging in my office: an orange entrance into a dark passage in the depths of the Bryce Canyon amphitheater. Nearly 40 years later, some dear photo friends and I travelled to Hanksville, Utah, and then up the Notom-Bullfrog road through Long Canyon to the Burr Trail and then up to the Muley Twist road and the Strike Valley Overlook.

A decade is a lifetime in today’s photography. Reviewing my 2010 trip portfolio would give me a chance to apply what I’ve learned in these ten years, to provide better images, and to soar above my solitary land of the hunkered.

—

So off I went, back to the Golden Circle.

I’d wanted to drive the the dirt track up Johnson Canyon to Cannonville, so before I reached Kanab I turned north, anticipating the bright sights of the Bryce Canyon amphitheater. The land around Johnson Canyon, it turned out, was tan with hints of reds spread underneath a dusty rolling juniper woodland. This was different than what I remembered by Bryce Canyon. Why? My notes had the answer.

I imagined being a very persistent fly that could find walls and just ride them for a very long 2 billion years. What would I have seen? An earthly drama of grand scale would unfold. I would have been in a basin. Over time mountains could have been all around my location. Seas, rivers, and dunes could have replaced the mountains.

The result? Something like a layer cake was assembled, from the depths of the Grand Canyon (1.7 billion years old) and rising up some 7,000 feet to the top of Bryce Canyon (50 million years old), more than 20 sedimentary layers were created by evolving conditions of geography and climate: wet, dry, seaways, lakes, rivers, dunes, each step overlaying horizontally and compressing the previous steps (maybe 10,000 feet down). 150 years ago this layer cake was named The Grand Staircase for these layers.

Johnson Canyon looked different that Bryce Canyon. It’s 40 miles, as the raven flies, from Bryce. It resides at 3,000 feet, stairstep 18. Bryce is at 9,100 feet, stairstep 27. We weren’t there yet.

Having figured this part of the geology out, I continued up the road. When I started my 2010 ramble, I was a landscape photographer, mostly film, just converting to good digital equipment. I was ready for a landscape show. People and their clutter were a distraction. So what did I find? Humans, cowhands with their cattle (slow elk, according to my friend Mark). I smiled and tipped my baseball cap, They smiled and tipped their Stetsons. I remembered that even Muir had to deal with livestock, in his case the sheep of his employer (“hooved locusts”).

As I waited, I watched the clouds rolling above me. It was October and anyone who’s traveled on these backroads knows that the rain can produce Utah muck, tire coating, wheel well filling, slippery soggy earth. (I asked someone once what to do if you get stuck out there, he said: “come back in the Spring”.) Delays were concerning.

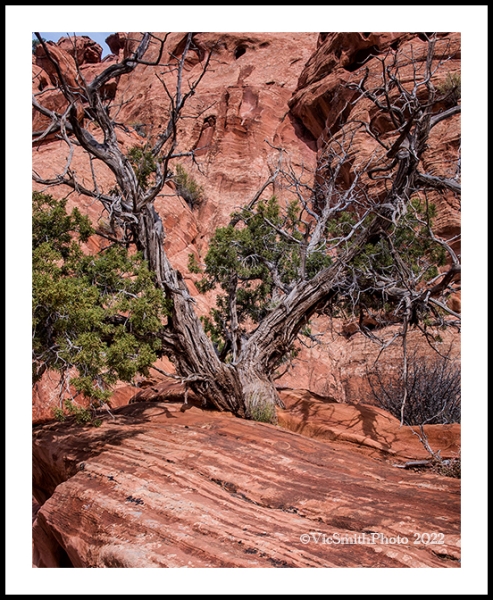

When the road cleared, I went on. On my left I saw the outcropping of sand dunes, the 1,000 foot thick Navajo Sandstone (190 million years old, layer 18) that had covered much of the arid west. This beautiful layer will outcrop again and again during the trip, during and after the Bryce time.

Johnson Canyon Rd. joins with Skutumpah Rd, so labelled by John D. Lee, the infamous guy exiled to build a Colorado River crossing at Lee’s Ferry. He first owned a ranch near my path. “Skutumpah” was borrowed from earlier people, the Paiutes, as an economical label for “an area where rabbitbrush grows and squirrels can be found.”

Weather shows current climate. Powell made me aware that this land is arid. Starting at Dodge City, KS, moving west, American land dramatically changes from well-watered to arid. There are two dangers aridity: thirst and flooding. I had enough water to slake my thirst. I soon found the dangers of flooding, in side channels as wide as the graded road, and then in a slot canyon, Bull Valley Gorge, 0.9 miles long and 100 feet deep, that still contained an old pickup that had slid in and killed its two occupants.

I kept driving, through a rain squall and then some mud. When I arrived at the red brick Cannonville BLM Visitor Center a ranger asked, “you came up Skutumpah?” When I nodded, he smiled and shook his head. I caught the pavement and saw a breathtaking view of the Aquarius Plateau under cloud cover on my way to catch up with Rick and the others.

—

The next morning the clouds had turned to storm, cloudy and cold. Rain had fallen overnight. From our 9,100 feet perch at Sunset Point, we saw the sun poke through cloud gaps to lift the white, pink, red, orange spires, walls, passageways into brilliance. We saw pines, spruces, firs, junipers, aspens, oregon grape, ceoanthus, and manzanita, all brightening into the light offered them, while hanging on for dear life in the friable Bryce soil.

After breakfast we sampled the other viewpoints, watched the clouds and fog, and walked the rim trail. Following a trail into the depths would have been exciting, but the sloppy verticality made it impractical. We enjoyed an early dinner at Ebenezer’s (that’s Bryce, not Scrooge). Back at our meeting place, we shared the magic with each other.

How did this brilliant show get produced? By Muir’s “pure wildness”? Yes. For me this had been a moist day in an arid land. But If I had again been that show runner when the production started, I would have seen the power of water along the edge of a 600 mile wide, 2,000 mile long intrusive seaway, warm and tropical, that inundated and split North America 90 million years ago. This was beachfront property.

This Seaway didn’t appear or disappear overnight. It rose slowly. Layers of water and earth borne sediments (limestone, sandstone, siltstone) collected at its edge. Then it slowly receded. This cycle was repeated, over and over, building new sediments and their colors, until it receded completely, leaving on a shallow lake, that continued the collection until its waters evaporated.

These collections are the earth in Bryce Canyon, the Claron Formation (one who lives near the River Clare). 700 foot thick, 50 million years old, layers of moldable textures and strong colors, with an occasional shark tooth appearing.

So there were the rocks of Bryce Canyon, lying at sea level. Then the earth’s crust moved and this land, the Colorado Plateau, rose. Why? There are theories, not much agreement. Nonetheless, the Bryce part of the plateau was eventually lifted to its current 9,100 feet.

What happens when earth is lifted to great heights? Water collects. It flows down, finds the cracks, the joints, and the faults and wears away what it can, creating the spires and walls and passages and revealing those bright colors. It creates Bryce Canyon.

It is still creating. As runoff from water flows east, the Bryce Canyon rim moves to the west, about 2 feet/century, by headward erosion. The show is always changing. (BTW, Bryce Canyon’s avg moisture is 9.5 in, so it’s a desert.)

That’s the land. What about its stories? Long after the erosion of the Claron Formation started, humans arrived. The earliest hunter gatherers entered about 12,000 years ago, leaving but scant evidence of their lives. Then about 1000 years ago, Paiute people started to appear. They looked at the colorful spires as beings that became bad, turned into stone by Coyote, the pillars and rows of rocks, are their “red painted faces”, actors in a morality play.

When Americans came, they saw land for ranching. Ebenezer Bryce arrived in 1875, sent by Brigham Young, built such a place and left the still-remembered description, “helluva place to lose a cow”, before moving on. (Maybe not before building a restaurant on the rim?) Another rancher, Ruben Styrett, built Ruby’s Inn in 1916, about the time that the Union Pacific railroad expanded service into the area. In 1928 this land was protected as Bryce Canyon National Park.

Bryce Canyon: built from the earth by the earth.

—

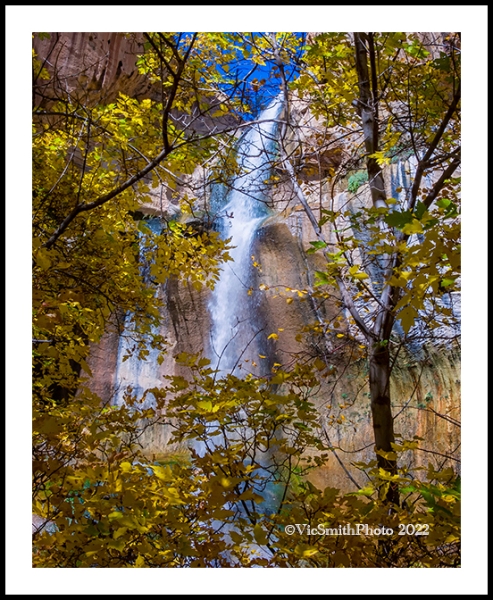

Then we moved on, toward Boulder, Utah, and Capital Reef National Park. Along the way we stopped at an oasis, Lower Calif Creek Falls, a narrow stream dropping 88 feet over more of the Navajo Sandstone dunes, Navajo Sandstone, before trundling down to the Escalante River.

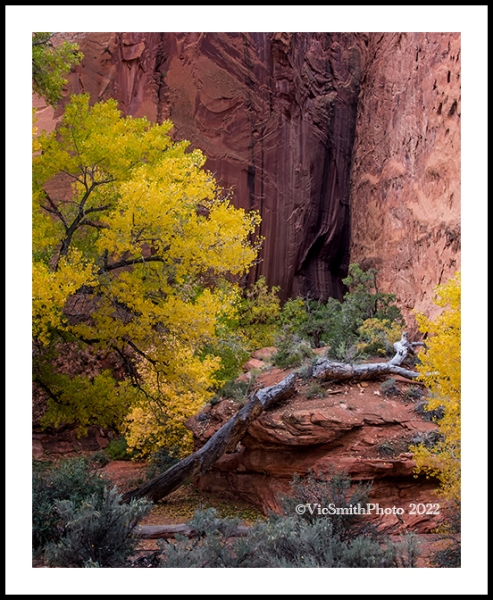

At Boulder we turned onto the Burr Trail passing the Muley Twist Road and then down the Waterpocket Fold to Capital Reef. Our goal was Long Canyon and its cottonwood alcoves. We stood with our tripods below the walls of rich red Kayenta Formation. This was sand collected from high mountains (ancient Rockies), then carried by rivers across an arid land. It now stood, cut by ephemeral water, in 350 foot walls, buried beneath the 1,000 foot Navajo Sandstone dunes. Water was an important part of this arid land, then and now.

—

So my escape ends and I return to my cave, now with treasures dancing around me.

Bryce Canyon is a narrow strip of magnificence surrounded by domestication. We traveled on asphalt roads and visitor path. When I look at my images, I see land beyond the colorful spires, the land of dark green. Those are towns, Tropic and Cannonville, and ranches. The water that is carving and widening Bryce Canyon is flowing down into the Paria River is diverted to feed the ranches and towns.

Yet within their own spaces, what I saw the wild and it swallowed me. The arrival and the flow of water, its erosion, and the earth’s response are unpredictable (is that the definition of “the wild”?). The areas I saw don’t have the scale of Muir’s High Sierra (few do), but they surely make my spirit soar as I watch water and light continue to work their magic.

I think of Bryce Canyon more on the scale of the west Portals of Notre Dame, The Portal of the Last Judgement, the Portal of the Virgin, and the Portal of St. Anne. They are unforgetable, opulent and magical, great gifts of creativity, fruits of a creative (more wildness?) spirit.

Bryce Canyon is intoxicating. I’m glad that I’ve taken the time to leave my cave, rework my images, and relive warm memories. For me the thrill will always be the shoot. These images will have to do for now, but I am renewed and will stand in these places again. I will walk into the canyon, through a passage, touching the jointed wall, and back into the light. I will stand at the bottom and look up to the rim. And then I’ll climb out and enjoy a warm breakfast.

Thanks for joining me.

All images and words are ©Vic Smith Photo 2020

**this piece is excerpted from a longer work intended for publication submittal

**please contact me (vic at vicsmithphoto.com) if you are interested in reviewing it

201221-VSP