My imagination is at the center of my being. In the midst of obligation, my imagination can arouse and waft away in a kind of walkabout scene. I quickly seek my center places, gather my history and build on those places and times. The scene can be in woodlands, sometimes in the midst of humans and their artifacts, more often the scene has been in a space I’m calling Desert Magic (RJ Garn), like a Maynard Dixon print.

It is this part of my history that I want to share.

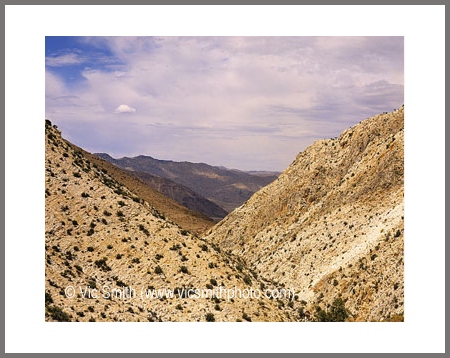

The canyon walls on either side of me were mudstone and conglomerate, light tan, glowing in first light, and crumbly, inviting me to touch. A light December breeze brushed my face. The canyon wound out of view below a dark ridge, crisp in the starkly clear air.

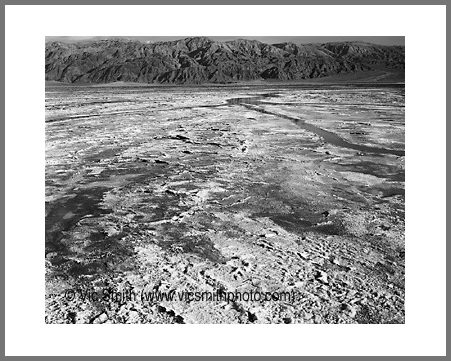

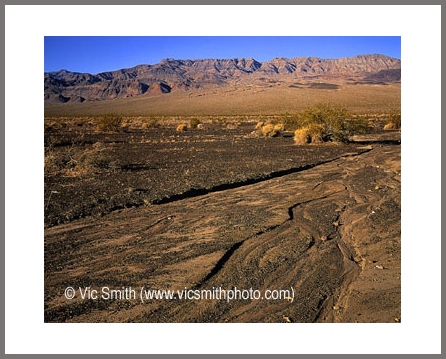

Above me to my right was a ridge with a short access trail to another ridge, an overlook, Zabriskie Point. From there I could see my former path down in Gower Gulch, its surface flat but marked with the leftovers of former flash floods. The gulch disappeared through Golden Canyon.

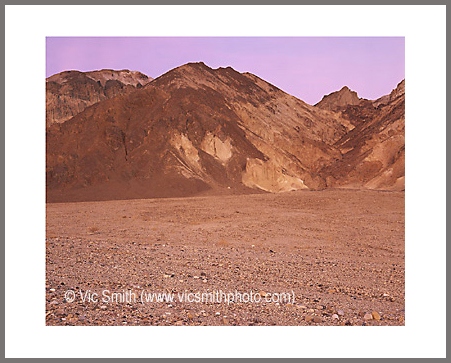

Directly down from the point was a jumble of colorful striped ridges, clays, silts, gravels, and volcanic ash deposited in a now vanished lake, then uptilted. At its left end was a tan tilted peak leaning to the south, Manly (remember this name) Beacon. To the right above was is a flat cap, like a sill, of flat dark volcanic earth, completely different from what’s below me. If I had climbed high enough on the canyon wall we could’ve seen, 40 miles away, a snow capped peak.

This was Death Valley, found in eastern California near the Nevada border, a rocky shrine for desert rats like my rockhounding father who reveled in its textures, its colors, its solitude, its pristine clarity, its monumental scale, its extremities, its seeming eternity and its minimal reminders of human occupation. He brought our family here to share those times.

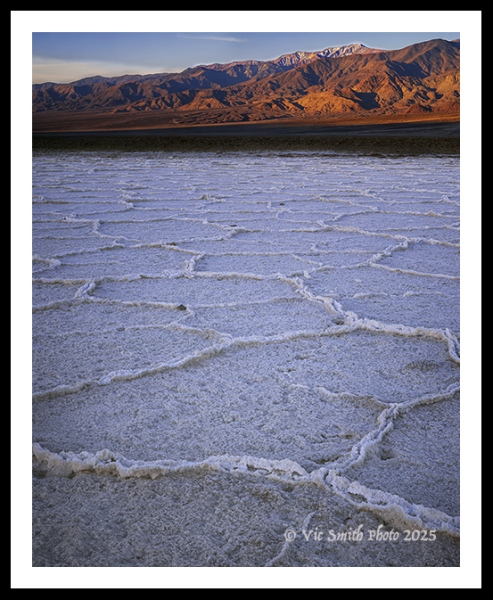

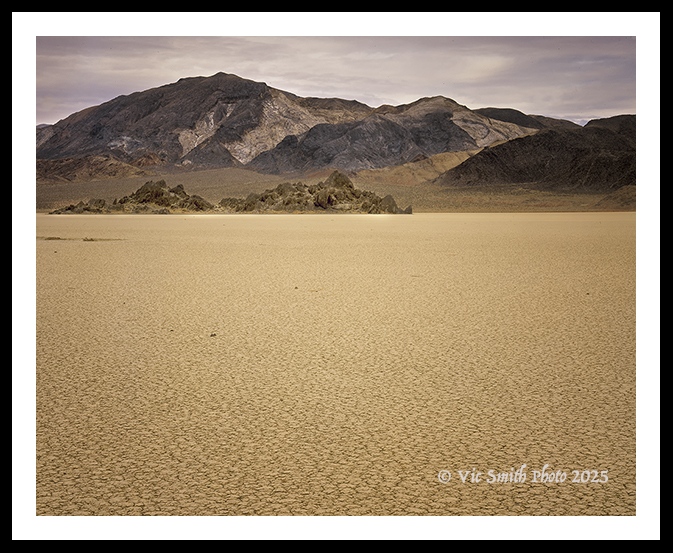

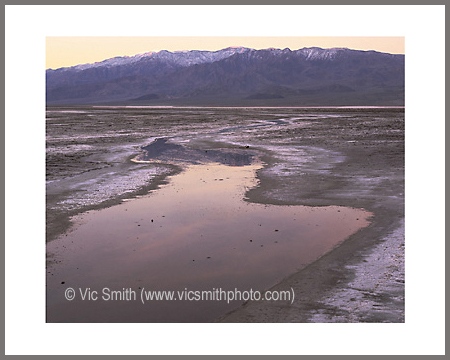

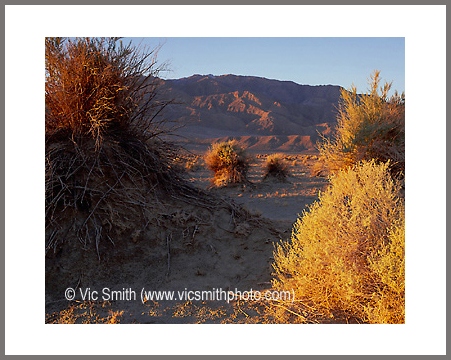

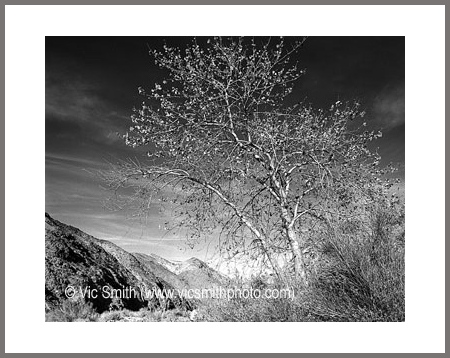

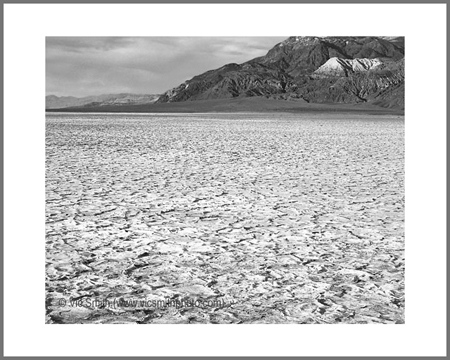

In the years since our family romps I’ve been infected with the mission of finding and capturing landscapes in photographic form. Here are some images, mostly captured some time ago using what my travel companions came to label my Big Bob camera on 4” x 5” transparency sheets and reworked recently.

These represent but a sampling of the available images. Please enjoy them. I’ve tried to guide myself around this place. (Please excuse any errors in photoshop masking.) If you want some of my guid-ish discoveries, the land, life on the land, and that devilish name, please read on.

Eastern California, the locale of Death Valley, is a complex region formed by large land masses jamming into the developing western US over billions of years. Like the earth everywhere, what looks colorful, solid and stationary has had a complex history through space and time. Never forget that the earth never rests.

Death Valley National Park largest National Park is largest park in the continental states, 5300 sq mi, 160 miles long, Death Valley National Park. Within its bounds you can drive from an elevation of -300 feet at Bad Water, to an elevation of 600 feet at Zabriskie Point, then up to 11,000 feet at Telescope Peak. 150 miles west towers Mt Whitney at 14,500 feet in the Sierra Nevada (the highest point in the continental states). Reflecting this turmoil, you can also drive to a volcanic outburst and a failed continental rift.

Within the park are 2 mountain ranges, (the Amargosa on the east and the Panamint on west), and several subranges. Within this melange are 5 major valleys. The rocks in the ranges date back nearly 2 billion years (almost half the age of the earth).

Like the Sierra Nevada, the mountains are the result of two tectonic plates (Pacific and North American) splitting from each other in angular paths. The lands have then been stretched and have torn, causing large blocks of crust to be thrust up as down-to-the-west mountain ranges. The split is continuing and so the mountains are still rising.

Death Valley is a land of extremes. Temperatures range from 15°F to 129° (a competition with Kuwait). And Death Valley is famously arid, with sky water often less than 2 inches per year, often by localized flash flood on steep slopes and across loose earth, often wiping out the roads crossing that soft earth. This aridity and heat make Death Valley National Park demand caution for those who wander.

For Example: DVNP 9/19, 3:30pm:

Storm Impacts in Death Valley National Park

The remnants of Tropical Storm Mario brought 0.6 inches of rain to Furnace Creek on the night of September 18—about one-quarter of the park’s average annual rainfall in just a few hours.

In a desert like Death Valley, even small amounts of rain can trigger flash flooding. The park’s rocky, steep terrain causes water to run off quickly, creating fast-moving flows of mud, rocks and debris. These floods have covered some roads and have eroded road shoulders, making travel hazardous.

In those arid valleys you’ll find more landforms, sand dunes and salt flats. Much of the land is covered by windblown sand. There are 4 significant sand dunes fields. Mesquite is the best known, Eureka to the north boasts a 700 foot slide. They have also been where locals found water, in trapped aquifers fed by rare creeks.(Stovepipe Wells comes from a stovepipe somehow sunk into the sand and reaching the aquifer in order to support vagrant miners).

Much of the west is old ocean crust, saturated with salt minerals and clays. When water flows down into the bottom lands it collects, full of the salts and clays. Then it evaporates, leaving dense flats of mud.

Death Valley is a land of extremes. Yet life is all around there, critters and plants abide. 440 species of animals, 53 plant species.

What about humans, and that devilish name.

Europeans are very late arrivals. When they bustled in they found the Timbisha Shoshone people had preceded the American claims of grandiosity by over a millennium, on land given by the creator with the charge to find sustenance and to care for the land. The Timibisha weren’t into the grandiose. They named this land as “red rock” for what the creator had given them, red ochre. This necessary for ceremony and valuable for trade (like the Havasupai in Arizona). They took what the creator gave them, only extracting what they needed to sustain themselves.

Europeans changed the local dynamics. The earth went from being a gift to a series of inanimate objects. Sustenance became extraction, earthly care became exploitation, respect became greed. Finding a resource, e.g. a valued mineral on which a few profit, too often becomes degradation of an even more crucial entity, e.g. an acquifer on which whole peoples’ depend.

When I was young my brother and I watched Westerns and also “Death Valley Days”, with Ronald Reagan. We used borax soap and traveled on the 20 Mule Team road. Processed borax ore scraped from the Death Valley salt pans and carried to the railroad, 20 million pounds of it, worth $30 million.

We also read about Shorty Harris, one of The Ghosts On The Glory Trail, a “single blanket jackass prospector”, who prospected, gambled, and sold his findings and claims. Such claims led to discovery of gold and silver. Keane Wonder and Skidoo mines became successful. The Keene Wonder Mine left behind 18,000 structures and produced as much as 70 tons of gold per day. Their sites can still be visited.

Eventually the plundering diminished, the extremities won. The earth carried on. Death Valley is vast enough and hostile enough that commercialization or gentrification hasn’t been realistic. Its pristine character remains, until at least the next mineral discovery

Now we come to the current name, “Death Valley”.

In 1849 Gold was found at Sutter’s Mill near Sacramento, CA. A Gold Rush tsunami followed.. People coming from the east often travelled on variations of the Old Spanish Trail. After passing through Las Vegas (Meadows in Spanish), people would travel across the Mojave Desert. One party (the Bennett Arcane group), however, decided on a winter shortcut, on the advice of an inexperienced guide, William Manly (remember the “beacon” at Zabriskie). They headed along the west side of the valley, straight into the edge of the large salt flat into a mud gumbo.

I can tell you from personal experience that the gumbo isn’t friendly space for human boots or for conveyances with tires. The salt/clay gumbo reaches out, captures the tire tread and fills the wheel well, capturing both propulsion and steering and encasing the exterior. My white SUV was fully mudded, even up the middle of cab roof. I couldn’t stop or I would sink. A flattened accelerator moved me forward, but with an unpredictable bearing. .

The wagons sunk. The oxen sunk. No one was going anywhere, the oxen were being slaughtered for food. It snowed on them, giving non-brackish water, probably saving their lives. Manly left to get help. He walked 150 miles to the southern San Joaquin Valley and came back a month later with supplies.

The members of this party were easterners, not explorers, so by the time they got stuck and then got rescued, they were desperate. One man who had been ill much of the trip died before reaching safety. Upon their exit over Wingate Pass, someone is rumored to have looked back and said, “Goodbye, valley of death.” A legend was born (look up the Bennett-Arcane Long Camp in DV for more of the story).

Ironically, Death Valley National Park is one of the deadliest National Parks in the system, now like in 1849 because people underestimate the extremities of the region and do silly things, like wandering in extreme temperatures without enough water. The legend prevails, because of tourism.

Despite the name, despite the human artifacts, I always think about Death Valley as pristine and inviting. I still appreciate it. I’ll get back.