A two-lane highway pushes south in front of us, through a land that looks old and slow, big trucks going by in a blur as they head north. My wife, her parents, and me are on a July day trip. We are following the meandering Bitterroot River up through its valley. Our starting point was in Hamilton. We are headed to a barn in another river valley.

More Images

Snowy Peaks

I’m not driving, so I look up to the big blue sky on the west, then at the Bitterroot Mountains, a part of the Rocky Mountains. This is Big Sky Country (it said so on the license plates for four decades), infinite sky, big craggy mountains, unlimited possibilities. The Bitterroots don’t disappoint. Their peaks look old and hard, granitic grays and metamorphic browns, like the fabled Sierra Nevada Mountains.

When the clouds of winters gather around the peaks, the snows collect. Some north-facing sections still sport small remnants of last winter’s snow. As winter turns into spring, the snowmelt flows down, through the weak places, gathering power as it hurries, collecting soil, carrying it to the river and the valley below.

Rising up toward the peaks are steep forested slopes with deep canyons gashed into them. Ten thousand years ago, the slow blunt force of glaciers cut the canyons and reached the valley through we are traveling. Glacial melt and till joined with the water backed up from the glacial dams to the north, forming the valley floor.

Signs of humanity in this valley are not as old as the earth, but neither are they new. Humans have been in the area for at least 12,000 years, arriving from Eurasia just as the last glaciers were melting. A thousand years ago, ancestors of the displaced Salish people were living here. Europeans arrived 150 years ago.

As we drive, we pass signs of domestication, small fenced fields, some with cattle munching on local hay, some with tall grasses, some baked dry, and some with standing water, small groups of whitetail deer eating at the edges of fields, and a Family Dollar store.

If we had passed this way two hundred years ago, we would have seen different evidence of domestication. The Hamilton area was called “Scattered Trees Growing on Open Ground” by the Salish because the grass was regularly burned to stimulate new grass and draw wild game that could be hunted. “Trail for moving camp”, the West Fork was a well-known trail along which the Salish and New Perce moved between the Bitterroot and the Selway Rivers.

We cruise past scattered houses among the fields, some new, others old, few of exorbitant wealth. Some houses are orderly, but others look cluttered, with beat-up cars and trucks, quiet farm and garden equipment, horse trailers, fence posts and assorted gray lumber. This stuff is their stash, the place where they would go if an inexpensive, timely work-around is needed quickly.

As the valley floor narrows we pass Darby and Ross Hole (Sula). We climb, going back and forth on switchbacks, past a portion of the South Nez Perce Trail (Nee-Me-Poo), climbing 4000 feet up to a pass. The Bitterroot peaks recede in our rear view mirror as we turn east across high ground, dropping into Dillon, and turn north, along the broad north-south valley of the Beaverhead River, toward our end point, a large cattle ranch and our large red barn.

Rolling brown hills run off on the left and the right. On the right they are dry except for bull-dozed cattle tanks. In the distance on the right are the Tobacco Root Mountains with summer clouds forming over them. On the left, the land tilts down to the river, where fields of hay are flourishing. Beyond the fields and the river are the Pioneer Mountains, another sub-range of the Rocky Mountains.

The Barn and The Bull

This trip is a homecoming for my wife and her parents. They lived in this area for several years in the 1950’s. During that time they became friends with a local rancher, Byron, whose family raised prize Hereford cattle. Byron’s lands once included the Doncaster Barn, big and round, originally built to house and train race horses through the winter. When hereford cattle replaced horses, the barn became a place for cattle sales and for local socials. It was now 100 years old. Byron was a success, a hero to many in the area and in the hereford business, having shipped twenty thousand head worldwide. His family and friends are gathering in the round barn to honor him, the barn and their ranch signs of their success. We are here to congratulate and join in the fun.

The party-goers range from the nineties to tiny new-borns. Many of the visitors are extended family. Most are still local, others from a ways away. (“Neeew Yoork Citee?”) Others people had worked for the ranch. Still others have neighboring lands and had bought Byron’s cattle to build their herds. Most are in some part of the cattle business. Many look like they’d just come from fields and ranges still with their cowboy hats, boots, jeans and stories about mosquitoes. They are steady in voice and in story, strong individuals and important parts of this community.

We watch and listen as photographs are shown on a screen and Byron tells stories, sometimes chiding, often laughing, and always thankful, about many of those in attendance and about the cattle that had been had raised, mainly the bulls, like Evan Centurian, Montana’s first $50,000 bull (we say his picture as we entered). He had told my father-in-law a story of finding two such large bulls fighting in a field. He couldn’t let them damage each other. All he had was his truck, so he put the truck between the bulls, absorbing the blows from each side until they tired and went their own ways. The truck was a tool from his stash, one that could be fixed easier than a bull.

I am not a rancher or ranch hand (I’m from “Californeea?”; slightly worse than “Neeew Yoork Citee?”) but I do respect ranchers for their achievements . The Bitterroot Valley is sometimes labelled as the “Palm Springs” of Montana because the Bitterroots block the coldest extremes and provide a more temperate climate. The Beaverhead ranchers live in a land that can be more severe: higher elevation, open ranges, cold storms from the north, -40 degree winter temperatures, 100+ degree summer temperatures, drought, rains that bring flash floods.

I am sleepy from lunch and my recently-repaired knee is a bit achy, so I walk out of the barn and around the grass surrounding it. I choose a rock and sit on it. At the barn entrance I again see the painting of the large bull.

The Buffalo

My memory goes back to earlier times, when I came in from the south, over Monida Pass. I remember that I saw a large statue of a a buffalo mounted on a promontory, a single buffalo (technically, an American Bison; there are no buffalo in the Western Hemisphere, but people call it “the buffalo statue”).

As the shadows lengthen, we say goodbye and thanks for the hospitality, driving back into the mountains and back to our valley. We return down the valley and on to Hamilton. Along the way I’m wondering about the buffalo. Surely such a site as a buffalo jump had to mean that there were once a lot of the animals around this area. I’d seen the big bull, but no evidence of buffalo. What happened?

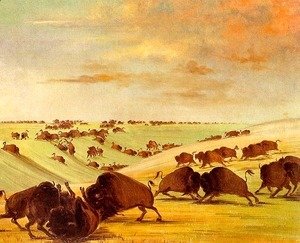

There were once many buffalo, according to sources like western painters, like Russell, Catlin, and Bierstadt, dramas and books about the early western occupation, and places like Buffalo Jump State Park a place where buffalo herds were herded off a cliff, to be harvested for the resources they offered. Surely a revered place like a buffalo jump says that there were once lots and lots of these bovines.

Indeed there were. The water and soil that comes from the mountains today feeds cattle herds, large and small. Before that, it had once fed vast herds of buffalo. The Eurasian immigrants had crossed over the Bering land bridge into North America, two hundred thousand years ago. In the West, they found grass and water, and prospered, numbering more than twenty million just two hundred years ago.

Buffalo were followed fifteen thousand years ago by more Eurasians, the native peoples who settled throughout the Americas, including the two valleys. Buffalo became central to them. Hunting parties travelled long distances, through the lands of allies and enemies, building lives and cultures around the bison, prospering with food, shelter, warmth, tools, weapons, clothes, utensils, and trade goods. These people worked hard, were resourceful, and prospered. It’s estimated that in 1491, before Columbus, there were more people in the Americas than there were in Europe.

Two hundred years ago a team of thirty three Americans entered the Beaverhead valley in search of a path to the western ocean, the Pacific. The Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, had been sent from St. Louis up the Missouri River by President Thomas Jefferson to find the path and lay claim to its lands for the hungry young country further east. According to the journals of Lewis and Clark, the Beaverhead was Jefferson’s River, the pathway to the Pacific. As they travelled up it with blistered feet, torn clothing, and empty stomachs, they were led through prickly pear and mosquito clouds by a native lady, Sacajawea, who had been born and raised near its headwaters, just below a pass, now called Lemhi, (see my earlier tale about my visit to the pass) on the Montana/Idaho border, then kidnapped by another people and taken east, where the Corps had been given safe harbor by the Mandan the previous winter. She agreed to guide them to her ancestral lands, the headwaters of Jefferson’s River just below the Continental Divide.

By the 1870’s there were less than a thousand buffalo in the West. Where did the buffalo go? (it’s a trick question)

Americans eager for their own land followed the path of the Corps and came into these valleys, bringing their Manifest Destiny, their eastern lives, their livestock, and their Army. The government wanted land for those newly-arriving so they put native people on very restricted remnants of their ancestral lands. General Phillip Sheridan (“the only good Indian is a dead Indian”) told them how to keep them there: “…make them poor by the destruction of their stock…”. Thousands of buffalo hunters came, sometimes averaging 50 kills a day, turning the ground into massive eerie graveyards filled with bones. Starvation and banishment of the buffalo peoples followed.

The Corps continued their trip. Having left the Missouri River, they needed transportation. Sacajawea’s brother, Camehwait, chief of the Akaitikka Shoshone, took them in, and traded them horses for the promise of guns (which were never delivered). Camehwait was getting ready to lead his hunters to hunt buffalo.

Then the Corps needed to get over another pass across the Continental Divide, known today as Lost Trail Pass, the one that we had crossed earlier, (their new Shoshone guide, the nearly blind Old Toby, didn’t really know the way and got them lost on the 4,000 foot climb to the pass). The seasons were changing as they finally descended, leaving them exhausted, cold, and starving. This could have again been the end but for an encounter with the native Bitterroot Salish, near what is today called Ross Hole (Sula), at the head of the Bitterroot River and its valley. When they met, the Salish were waiting to join with Nez Perce, enroute to the buffalo country. As was their custom, the Salish took pity on the struggling strangers after judging them safe, and provided food, including bitterroot, and shelter, thus walking into the crosshairs of the coming onslaught.

From there the Corps moved north through the Bitterroot and west on the Nez Perce Trail to their goal, the Pacific. The Salish, who had lived along the Bitterroot and hunted buffalo for a millennium would suffer a fate similar to the other buffalo hunters as easterners entered the valley.

The rancher had shown us gracious hospitality and shared their prosperity. Native peoples along the path of the Corps showed them hospitality and shared their prosperity. I suppose that life has an imperative to survive and, where possible, to prosper. Native buffalo hunters did that for a millennium. Ranchers in these valleys have done it for a century and a half. Each believed that they’d been given the land. The stories of the peoples of these valleys have rightfully been about brave, hardworking folks overcoming hardship and severity to create and maintain life. More than once they’ve also been about conquest and exclusion, stories written by conquerors to justify the conquest.

More eerie reminders of the conquered and their lives are kept around each valley, like the state park at the buffalo jump, celebrating the lives of native hunters and lands to the north of the Bitterroot, where the Salish were banished and still live. In the Beaverhead, there’s a fancy restaurant named after the once-dominant buffalo. In the Bitterroot there’s a town, Victor, named after the last chief of the Bitterroot Salish. And then, in a particularly ironic twist, the name “Bitterroot” is itself a name given by the Bitterroot Salish to a plant that they found essential, its pink flowers showing where its nutritious roots hide. And in a supreme irony, these roots provided the nutrition that saved the Corps.

The Dilemma

We saw two valleys, snowy peaks, rivers, a barn, a bull, and a statue of a bison. We enjoyed hospitality and delicious beef stew, and we enjoyed a tale of good fortune, diligence, and prosperity. But all this came from a past, one that is rumpled, not just what it seems, a past that loiters and haunts.

My wife asks me, “this was a wonderful story about a good time, why put the other stuff in there?” I say, “because it is there.” Our comforts can come with a price tag.

**this piece is excerpted from a longer piece being prepared for publication submittal

**please contact me (vic at vicsmithphoto.com) if you are interested in reviewing it

My thanks to Jessie, Rich, Larry, and Bob for their review

D227