Comes The Rain

I’m in my truck searching in the American West for the primordial magic of water. I’ve felt it in deserts, along creeks and rivers, and in the channels used to move water for human use. I’ve found it hiding, trickling, roaring, grabbing, and disappearing—always important, not always predictable.

My path today leads through high desert land that doesn’t readily show its water. On the left, the land stretches over short rises with shallow rounded valleys tilting downhill, giving brief glimpses of canyons. It is sandstone covered with pockets of loose sand, piñon pines, and sparse grasses. On the right are occasional houses—most have a hogan, corrals, and a pickup with a large plastic water tank in the truck bed. It is easier to drive for water than to drill for it out here. Loose horses lift their heads as I drive by, dedicated to the consumption of grasses fed by the bounty of road runoff from storms. Above me are clouds—puffy, small, long, and sometimes dark with rain or at least virga, maybe bringing gifts.

The paved road ends at a trailhead, and a short walk takes me to a viewpoint above a thousand-foot cliff. I’m standing on the edge of the east-west Canyon de Chelly in Northeast Arizona, part of a labyrinth of canyons extending tens of miles in each direction. It is a land of great scale, a place both long and old. The clouds seem to push the sky down onto the flat tops around me. Their shadows scoot through the canyon as they move between the horizons. In the eastern distance are the Chuska Mountains, extending fifty miles north and south.

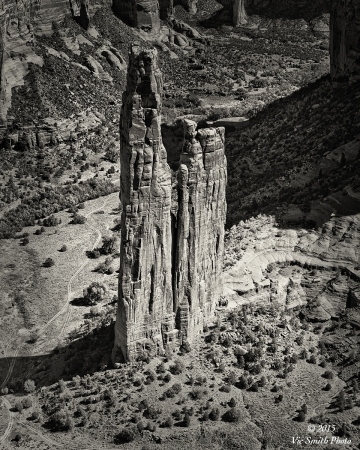

Two hundred million years ago, water, wind, and tectonic forces brought forth oceans, deserts, and rivers, depositing their shale, sand, and rocks. Then the earth moved, and the area was lifted. As the Chuskas rose, they attracted clouds that brought rain and snow. The fallen water traveled downhill, finding weak lines and eroding canyons. The erosion formed alcoves in the canyon walls, openings that often faced south and maximized winter warmth. Erosion’s path also left earthen structures, spires, and buttes, stronger remnants that deflected water around them. One such large spire, Spider Rock, rises nearly to the level of my vantage point, orange sandstone capped with the white rock of the rim. Water also sank into the sandstone walls, flowing down into water tables that have given stable water supply to the canyon’s living things.

Indigenous peoples found these canyons thousands of years ago. They found spiritual significance in earthen features like Spider Rock and attributed powerful stories to them. They also left more than 2,400 archaeological sites in their time here, sites like Antelope House, occupied from 300 AD to 1300 AD, sitting against a five-hundred-foot wall of compressed sandstone. The canyons also provided paths and way stations for people moving between places like Chaco in New Mexico and western Ancestral Puebloan settlements. Today Navajos inhabit family plots, leaving tracks along the canyon floor with their vehicles as they care for those plots and as they share the canyon with visitors. This place is their mother, and they are grateful for her gifts.

What I see in front of me is a big picture, in land and in time. When I look through the viewfinder of my camera, I see a smaller picture, one in which details tell stories. I see birds landing in trees with their wings spread, harbingers of rain and lightning. I see yuccas, piñons, grasses reaching upward in efforts to grasp some rain for themselves. I see a piñon, one among many, that reaches up, up above the distant horizon of the eastern mountains. It, like the other residents here, seems to be offering prayers for gifts of falling rain. The picture below me, in the canyon, includes narrow sandy washes that contain small pools, quicksand, hints of former flows, some small and some big enough to carve the canyon.

All of these pictures provide keys that begin to unlock the magic of water in the West, and of the life it brings.

Water Flows

The American West is a region of about 2 million acres. Its geography is varied, but its meaning has been uniform: the land of new beginnings. In the mid-nineteenth century several million people, following America’s Manifest Destiny, came west seeking those new opportunities. They moved into public lands that the United States had obtained through royal charters, old grants, purchases, and unjust appropriation of indigenous lands. The Homestead Act of 1862 promised 160 acres of this land to anyone at least twenty-years old and the head of a household who could stay there for five years. The US Government, real estate promoters, and railroads all sensed opportunity to affirm ownership and aggregate profits, so they lured homesteaders, American born and immigrants, men and women, freed slaves, to the new land.

Challenges arose in all of these places, but some had a critical resource, water. I was in one such place recently, Montana’s Bitterroot Mountains, near the eastern edge of the Rockies. My wife’s parents homesteaded here and established a still-standing family heritage. I was standing next to a creek that had swelled with spring’s thaw, as it has done for thousands of years, the water free to respond to the pull of topology and gravity. The clear water roared from its origins near the Bitterroot crest high above me, destined for the Bitterroot River in the valley below, hitting rocks that had been brought down in former floods, spraying up, filling the air with mist that covered everything and smelled of clear, cold water. The sound was tumultuous and seemed to come from deep within the earth. The wild water was foaming, tearing what it wanted, going where it would, and finding its own path, leaving greenery where it went.

Elsewhere in these mountains, I found another such flow, but captured into a ditch. The water was then pushed through siphons, fueled by its own force, and went where directed—over the river it would have flowed into, then under a creek. Along the way, for some fifty miles, it came to travel in an open channel, continuously eight feet deep and fifteen feet wide. There its path was smooth, and so its transit was calm. No rocks or plants roiled it. Occasional wind gusts rippled its surface, but the water was clear to the bottom. Its sound was different, emanating from the ditch and its siphons, not from the earth. It had been sent on a mission to sustain humans. The water was captured, moved past wild places to those where people raise crops, grow wealth.

Homesteaders in other areas, however, found different circumstances. They learned why the earliest American explorers had labeled the lands as desert due to its lack of precipitation and vegetation. Lewis and Clark, Thomas Jefferson, Zebulon Pike, Stephen Long, and many others came to see it as the Great American Desert.

Craig Childs has said of such lands that “there are two ways to die…thirst and drowning.” The former course makes the most sense to visitors. When I’m leading people into the backcountry, I say, over and over and over, “Be sure to drink enough water.” Those who don’t follow this advice often suffer.

I’ve learned the lesson the hard way, by running out of water. I was on a trip into the Grand Canyon with some friends, to a place temptingly named Clear Creek. It was in the spring, the time when snow water trickles down from the rims to the seeps and springs, when trees leaf out.

We started in the morning, hiking down the South Kaibab Trail to Bright Angel Campground, adjacent to Bright Angel Creek and Phantom Ranch. The drop was 4,400 feet over eight miles, so by the time we reached the refreshments at the bottom, I was exhausted and dried out, glad to find campground water.

Dawn the next morning found us loaded and climbing up the shady trail a thousand feet to the Tonto Platform. Somewhere along the way, because of some combination of false confidence and sheer foolishness, I decided I needed to save my water. As the next eight miles and eight hundred feet of undulating aridity passed, I willed myself on.

Two of our four-man crew wilted and headed back. Now we were two, Ken and I. On we went. The rocks in the washes through which we climbed got hotter and hotter, and I began to feel my error. A water deficit isn’t easily made up. So I started drinking longer, watching as the level in the upturned bottle got lower and lower. Then we still weren’t there, and I was nearly out. I sat down, seeking shade. This helped but didn’t get me any closer to our destination—or more water.

Ken relinquished his lead, returned, and shared his water and wisdom with me. I stumbled on, passing the upper edge of a big canyon, Zoroaster, and finally seeing the canyon that holds Clear Creek. One problem remained: I was now close to consuming all of both our water supplies. Beyond that, the final approach was a challenging downslope over rocky terrain, further straining my dehydrated, cramping legs. Down we went. When we reached the sandy bottom, Ken filled my water bottle in Clear Creek. I sat against a rock and drank from it, feeling its flow sustain me as it had the life around me—the trees and bushes moving in the breeze, the critters inspecting me as they scurried by my rock. I had learned a dangerous lesson and now appreciated the gift of the life I’d found.

I had lived in the desert for twenty years but had never really learned the arid realities of this place. I had always had a faucet near me and regarded its water as infinite. Suddenly it wasn’t infinite. It was hidden, and the land that I treasured was stingy with its bounty.

Other trips have taught me about another of water’s behaviors: its ability to drown. The Paria River in Southern Utah is normally a narrow channel of greenish mud trickling in a wider bed of former flows between widely separated cliffs. Once, I was standing on a sandy ledge, watching the complacent muddy flow when it widened and rose a foot, in seconds. As the sand at the edge eroded toward me, aqueous greenish mud, shrubs, and large tree branches approached and passed me at 20 miles per hour. The air was thick with earthy, laden smells and the sounds of a churning sea that was eager to let go of its living cargo. This seemed like danger in the raw, a southwestern “gullywasher,” a flash flood. Two feet of water flow can carry an SUV. Thankfully the flow abated, returning to its lethargy, and my ledge survived.

Not far downriver the cliffs come together to form the narrows of the Paria. The wider water squeezes itself into these narrows and marches down to the Colorado River. Along the way it passes slot canyons like the Buckskin Gulch, a deep slit in a sandstone stack that towers above its visitors, half the height of the Empire State Building and as narrow as an arm’s length.

What happens in a place like that when water like I’d just seen crashes through? It scrubs and propels everything in its way. I’ve hiked into the Buckskin, stood below its water-scoured walls. One time I found a fifty-five-gallon metal drum impaled in a rockfall. Now I imagined what a twenty-foot wave would look and sound like coming down the canyon toward me in that cathedral of stone.

Despite intermittent inundation, life remains in these desert places. The Paria plain has bushes and trees, cottonwoods and junipers. The canyon of the Paria is a riparian zone with cattails, reeds, and rushes. Even the Buckskin Gulch gives life. There are beautiful maples as well as sandy hills with grasses atop them and, if you look up at night with a flashlight, skunks. If you look down, you might see tiny pools with iridescent glints—the remnants of fish that appear when the pools form and whose only goal is to live long enough to leave eggs that can survive the coming aridity.

But water doesn’t have to flash to show its tempest. It can simply accumulate. I live on the Colorado Plateau, where snow falls in the winter and monsoons fall in the summer. The moisture collects in small washes, which then flows into canyons. These aren’t pretty like the Paria narrows or Buckskin Gulch, and they don’t have the same drama. There aren’t any sculpted sandstone or sandy floors. The bottom is a random jumble of small to large rocks, tumbled but still jagged. The sides are more rocks mixed in with shrubs and small trees, many of whose leaves have been stripped by the waters and whose branches have caught upstream detritus. The water that comes through this channel has the power to move and shape, the power of a flood without the flash.

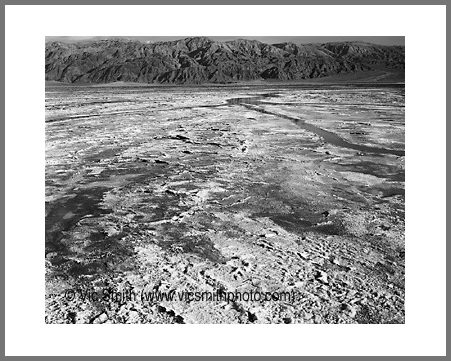

You can die of thirst or drowning in the desert. You can also get stuck. Imagine a place that invites you to cross and then grabs you with its slightly wet top layer of salty clay soil. I’ve spent an afternoon at the Bennett Spring in Death Valley, California, watching the salt pan of Lake Manly. Here moisture falls on the twelve-thousand-foot Panamint Mountains to the west and flows down to the lake, below sea level, sustaining plants in the seeps and marshes. From there it evaporates, leaving a mineral legacy.

I was in an SUV. All I had to do was to start the engine and drive out on the graveled road made by modern machinery. The Bennett-Arcane family had no such luxury in 1848. Their wagon wheels got stuck, near what is now known as Bennett Spring, stranding them. They sent a member of the party to get help. He returned weeks later with sustenance and supplies, and only then were they rescued from their watery bog. The Donner Party was not so lucky, getting caught in the Great Salt Lake Desert of Utah and tragically arriving at California’s Sierra Nevada passes too late to safely cross over the mountains.

Desert water can hide, it can drown, it can grab. Land promoters, abetted by the US Government, ignored these realities and told dreamers in vivid detail that gold coins, green rolling hills, refreshing June rains, and gentle Chinook winds would sustain them. It would be a garden. Rain would follow their plows. They didn’t tell them about the geographical line that defines a geography of aridity, the 100th meridian. It runs north and south through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. Land to the east of the line can accumulate twenty inches or more of precipitation—enough for traditional agriculture—while much of the land to the west gets no more than ten inches and can’t sustain traditional agricultural practices.

The people who moved into the desert out west were often thrust unwittingly into a land they weren’t prepared for and were given a model that wouldn’t work well. Theirs was a hard life, beset by drought, downpours, vicious storms, deprivation, economic uncertainty, and deprivation. Neither their crops nor their livestock had a good chance of surviving. Those who stayed on the land became the core of small new communities. Most didn’t stay, instead leaving for more watered areas in California and Oregon, often selling their homestead lands to those who remained. The survivors adapted their practices, acquiring enough land to support open grazing for livestock or changing the land with pipelines and channels to bring the water to them.

The experience of one family, the Dominys, came to shine a bright light on these projects. They had migrated from Illinois to Hastings, Nebraska. Their plot was high, dry country, unsuitable for farming, below even marginal. In the best years, it received fourteen inches of precipitation and would support only one cow. In the worst years, they faced drought.

A son, Floyd, witnessed these travails and formulated a response. He organized neighbors to join in the development of earthen water containment structures that would allow them to retain enough water to support themselves through the drier times. They learned how to control the gullywashers that had so often washed by in a flash and flooded settlements, saving water for future use and minimizing destruction. Floyd was not shy about the fruits of his work, and soon he had gained respect and influence.

The earthen tanks they built helped, but rainfall patterns were unpredictable and didn’t always go where they were needed. The settlers needed stability. As they traveled around the West, they had seen the mighty rivers that cut through it—the Missouri, the Platte, the Yellowstone, and the Colorado. But these rivers were narrow threads in a big land. What if they could capture river water and bring it to new lands?

Thus was born the United States Reclamation Service and its successor, the United States Bureau of Reclamation. Floyd Dominy joined the latter and eventually became its director. His belief was simple: wild, free-flowing rivers and the plants that grew in their ponds were wasteful. He reveled in the sight of wide, flat reservoirs captured behind concrete dams. The real value of water, he preached, lay in the capability to put it to human use.

The Bureau of Reclamation joined with the US Army Corps of Engineers in the mission to collect water for human use. They built hundreds of dams and associated water storage and power generation projects across the West, dominating the discussion between the Great Depression and the 1960s.

And the water flowed like that which I saw in the channeled water in the Bitterroot Valley. It allowed people to live in the desert with ease, growing crops, turning on the faucet for quick satisfaction, watering yards and gardens for all the desert to bloom. As water was supplied, it was also subsidized. Demand increased. The faucet needed to run faster and faster in a land where new supplies were slowing.

Dams are big and powerful, matching America’s spirit coming out of the Depression. But they manage just a small part of the earth’s freshwater. Engineers like Dominy soon realized that groundwater is the real prize to be collected. So they targeted aquifers like the Ogallala beneath the Midwest—one of the world’s largest—and those west of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California.

Aquifers that took millions of years to build are being depleted at steep rates. The Ogallala Aquifer is now being extracted at ten times the rate it’s being refilled. In California’s central valley, groundwater is, in areas, nearly one thousand feet deeper than it was just thirty years ago, causing the ground itself to sink thirty feet in some places.

In today’s arid West, there are too many people wanting too much too fast. In an all-too-real example, the water level in Lake Mead, the Depression-era monument to water extraction, is so low that its neighbor, Las Vegas, is constructing a drain below the lowest point to suck out the last drops for its casino fountains.

Approaching The Fork

As I’ve traveled, I’ve found water in many forms. I felt its plentitude tumbling down and spraying up from the crest of the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana. I’ve seen its scarcity as I’ve viewed the dropping bathtub rings of Lake Mead. Their differences are now stark. But they share a common long-term threat: climate change and the significant shifts in weather patterns it is bringing to every water source.

These shifts are increasing aridity and raising average temperatures. News about lowest snowpack, longest drought, and highest temperatures on record appear regularly in my newspaper. And the moisture that is falling isn’t reliably filling our monumental investments in concrete dams and flat-water reservoirs.

The road has now come to a fork. We have the choice of which path to take. One path is the acceptance of dwindling and compromised water and only requires that we do nothing. Another path challenges us to change our habits for a better future. There are people who have chosen the latter path and are successfully protecting water on their lands. They can lead us forward. They are modeling solutions both for the long term and for the present.

Addressing the global challenge of climate change is a crucial step on the long-term path. Since most of our society’s leaders are busy, dancing with a sputtering past, the actions to create a sustainable future must come from the people and be forced upward upon the leaders. This means defining and then embodying a combination of personal commitment, alternative solutions, and civil resistance.

People, especially indigenous people, are responding to this challenge around the world. They are fighting the attempts to increase extraction at the source, on their lands. They have discovered that the activities fueling climate change—extraction of oil, gas, and coal—are demanding significantly larger portions of flows that are smaller, often contaminating them in the process. The battlefields include New Brunswick and British Columbia in Canada and Wyoming and Montana in America, to name just a few. These people are committed to keeping their water alive so that their lives can be sustained as they build an alternative, stronger future that helps offset the inevitability of climate change. Their movements, often featuring women in prominence, are known collectively as Blockadia. This is progress.

There are also groups who have already established successes for specific lands and waters. Folks in the state of Washington recently stood at such a fork and made a decision that they could live without the benefits of two dams on the Elwha River. Both were removed, the largest such project in the world, and health was restored to that part of the earth. It would have been magical to see and hear the first wild water flowing again; watching fish, crabs, and clams once again thrive in the new estuary; watching salmon course upstream in what was once the richest salmon river on the Olympic Peninsula; and hearing birds call out as they descended to feed on the new bounty. This is progress.

There is another place where people have successfully fought for their water, California’s Mono Lake. The water from this beautiful eastern Sierra basin was coveted by the people of Los Angeles, but their water removal was ruining the lake and its vital life. Advocates rallied and fought to protect its life. Their solutions included applying unrelenting legal pressure on the power structure and building a common vision with people in Southern California—reduced consumption in kitchens, bathrooms, yards, and shopping trips resulting in decreased overall water usage despite a 25 percent increase in population. Now both the lake and the city’s people thrive.

I’ve stood many times next to the creeks that course from the eastern crest of the Sierra Nevada Mountains down to Mono Lake, filling this inland basin where life abounds. I’ve watched the coastal seagulls come to the lake to feed on brine shrimp and raise their next generation. I’ve watched shore birds peck at the bugs in the unfettered grasses that depend on the seasonal flows to renew and sustain themselves. This was once a major resting place for migratory birds, and they are returning. This is the wildness of life, and it is prospering. This is progress.

It’s time for us to replicate these events with other bodies of water across the country, around the world. It’s time for us to choose the right fork. Our earth is not a clock to be controlled. It is our mother, offering us the gift of water. Let’s rally to keep our water alive.