Water is a miracle. It appeared on earth not very long after earth coalesced solar dust

and gas to form its core. From this water, life quickly appeared. This linkage, life and

water, is still crucial to our existence and to our sense of well-being. Humans are 60%

water. We can live for a few weeks without food but only a few days without water. And

for the most part we find the sights and sounds of water to be a mysterious, soothing

and grounding experience.

I, however, live in the land of Sinagua, a Plateau without water. It is a name given by the earliest Spanish explorers seeking their golden cities but finding a land whose cinder cones, red rocky outcrops and treeless flats were the embodiment of aridity. Earlier inhabitants, the Ancestral Puebloans, knew how to prosper in this aridity. They know where to find the water that their life ways required. Their heirs maintain that knowledge, seeing water as part of a life-giving cycle in which it is treasured, protected and conserved.

Many who live here come from more watered areas and all too often expectations and policy have been driven by the misconception that life west of the 100th meridian should be the same as that east of the division. The history of water in the west has often been problematic because of the expectations and the boosterism of those promoting the region for their own gain.

Living on my piece of Sinagua land is especially challenging because we receive nearly 100 inches of snow each year. So as I’m shoveling, I already know that the water won’t stick around.

Yet there is little evidence of moisture other than snow, no natural perennial creeks or rivers and only one lake.

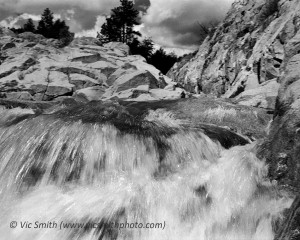

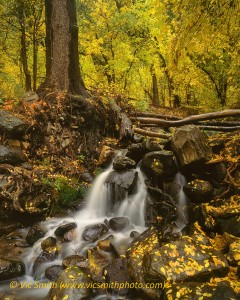

For a brief period in the spring, there are places of water.

But then it is gone and the only evidence is in the pine trees and grasses. Where does it go?

Like water everywhere, it goes down. It waters the pine trees at the surface and then

down into the limestone that forms the caprock on which I reside. It flows along surface

washes and then through cracks as it sinks deep, forming underground water courses

that can link together to form pools, can form rivers that seasonally burst out at

opportune locations or can trickle down and seep out in a steadier fashion.

I see all these scenarios around me. When snow is plentiful, my trees retain deep green

needles through the summer. The water that flows from my faucet comes from a pool

2000 feet underground, formed by the same fault that has created the modern Oak

Creek Canyon.

If I go to the Grand Canyon, in a good year

I can see the outburst of Cheyava Falls in

the Clear Creek area, a place that

the legendary Kolb brothers

investigated by climbing

into its underground course.

Or I can see the magic of Vasey’s Paradise, the brief but

powerful course of Thunder River

or the sound of Roaring Springs. All of these outflows

sink until they hit a harder layer and

then flow toward their exits.

If I go south or to the Little Colorado River, I can see the surface flows engorging washes, creeks and rivers. They join together in narrow canyons and then emerge to fill downstream beds well above normal levels.

And then the washes return to their normal dry state and the water that

emerges as small springs and seeps can be seen, filling the creeks with their normal

flows.

In short, the water goes many places and provides many magical moments. The water rises, falls and then the snow comes again and the magic is renewed and the cycle starts again.