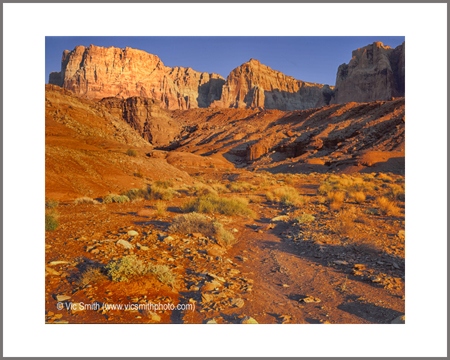

My truck bounces as it climbs to the approaching summit, gripping the wavy surface of the road as the asphalt seems intent on throwing me. The earth around me looks tipped and convulsed. The highway travels over flat sheets of red and tan sloping down under the road and on to a large wash, disappearing under the near side of the wash. The far side is bordered by large blocks, layered with reds, rotated so that the layers point back to the left, over the road, as if to say, “up there”, toward a cliff that doesn’t exist up there any more. More layers of southwestern colors, siblings of the fallen blocks, rise above them. These layers consist of slopes, bouldery, interrupted by vertical faces, rough and blocky. The crest is serrated. These are the Echo Cliffs.

Beyond the summit the view opens toward a wide yellow plain, the Marble Platform, running to the west and the south. Its surface is cut by a winding shadowy canyon, the bottom out of sight. This is the Marble Canyon part of a Colorado River river trip. “Colorado” means “red-colored” in Spanish. It used to be mostly red (“Colorado” is “red-colored” in Spanish) because it was a voracious consumer of southwestern red earth as it dug its way south through the Colorado Plateau to the Gulf of Mexico

Across Marble Canyon a broad scarp abruptly rises from the platform and obliquely runs toward the distant end of the Echo Cliffs, forming a narrow canyon. These the Vermilion Cliffs.

These Cliffs are a part of the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, a nearly 300,000 acre National Monument that includes the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness, the magnificent cliffs and the top of it all, the Paria Plateau. Together they form a little known patch of southwestern splendor. It is a place that draws me back again and again.

The Monument is a section of a larger Vermilion Cliffs geological structure, a part of the famed Grand Staircase consisting of multiple steps, the Chocolate, Vermilion, White, Grey, and Pink Cliffs, that start at the Grand Canyon and climb up to Bryce Canyon. The staircase Vermilion Cliffs are much longer than just the Monument, starting at the Colorado River and traveling toward Zion and including the Monument along the way.

The cliffs form an irregular horseshoe or a tipped Minnesota, with abrupt and sheer edges on the east side near the Colorado River, curving sharply around to the west and then shallowing. Roads surround much of the Monument, keeping the cliffs above much of the way. Carving through the middle is the Paria River, a muddy, quicksandy route that starts below Bryce Canyon, enters the plateau from the north and ends at the Colorado River. It is abetted by the Buckskin Gulch, a normally dry but flash-fillable slot that enters from the west and joins the Paria River in its narrows.

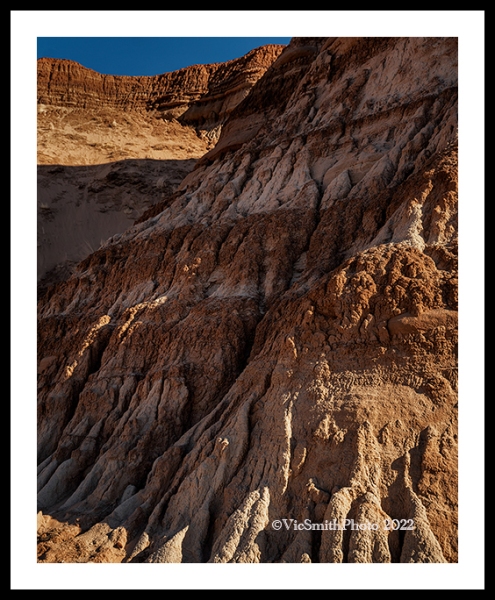

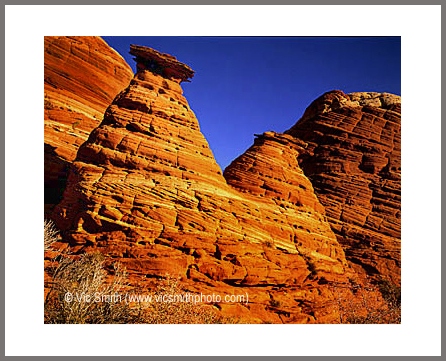

Wherever you see them, the Vermilion Cliffs beckon and challenge. From a distance, they make you look, rising sharply from a flat plain. Up close, they are humbling, rising above and in front of you in a tumble of remnants, debris, slope and cliff portions in many shades of red, topped by a thick layer of white. Their face is often rough, giving up to erosion mostly in blocks large and small. Their vertical sections poke out like resolute chins defying their fate. Small canyons have been clawed back from the face. Their crest and some of the canyons are dotted by the green of juniper trees. They collect water and then share it slowly.

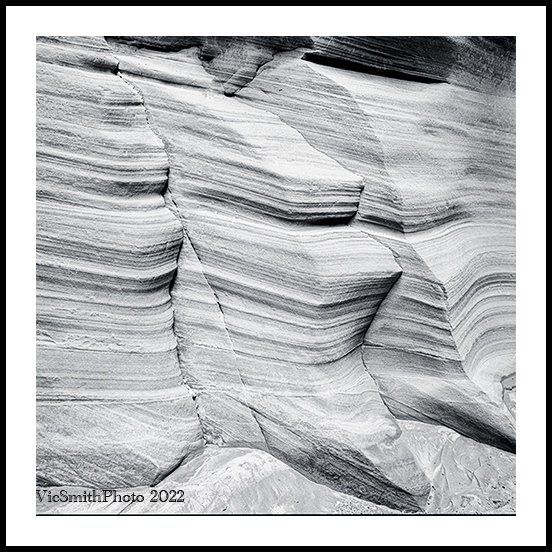

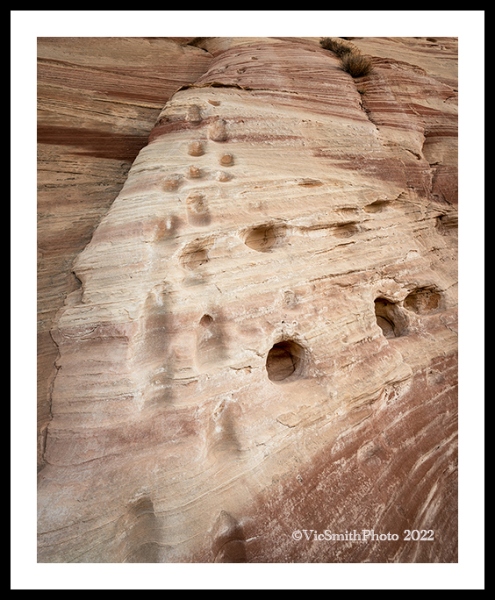

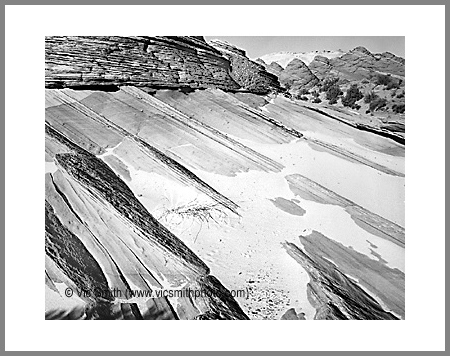

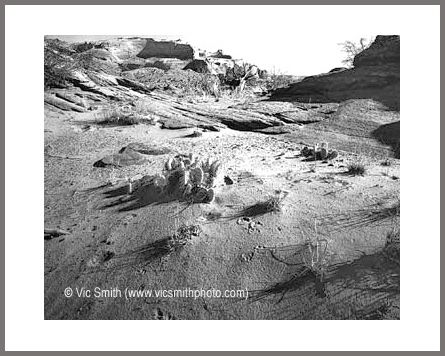

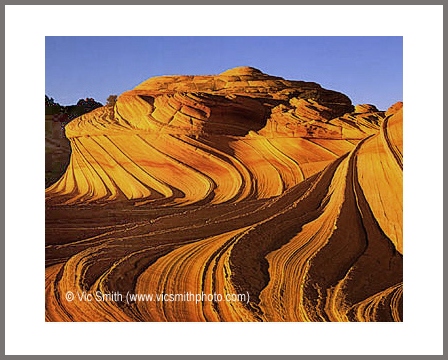

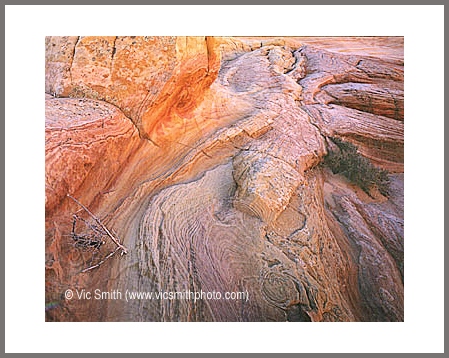

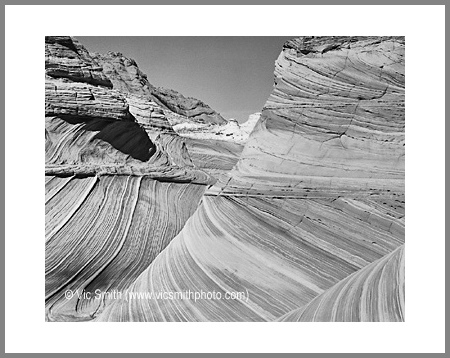

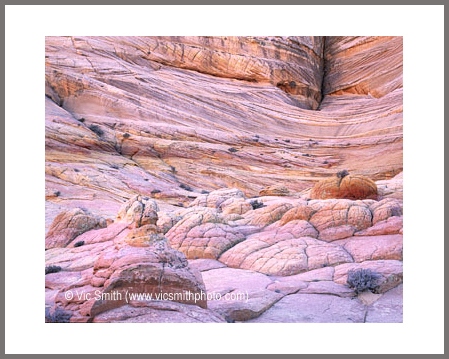

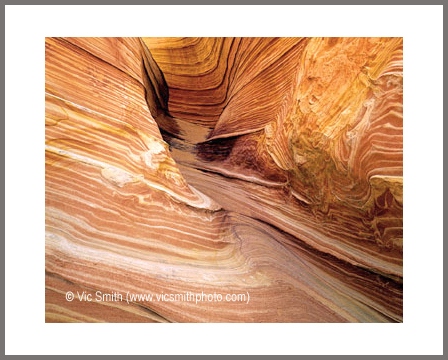

Their outside faces may be rough, but their interior faces are smooth. The west end of the Monument is the locale of Coyote Buttes, home to The Wave, a piece of a sandstone wave stuck in mid-break, and to the cliffs of Paria Canyon, sandstone piled high and then sliced through like with a hot knife. These textured layerings of weathered and flooded sandstone take your breath away. Walking up and placing your hands at the bottom of 200 million year old fossilized dunes and river sands is a rare opportunity to feel our earth.

A good first view of the cliffs is to drive down Highway 89A, across Navajo Bridge, to Lee’s Ferry. It’s where John Wesley Powell

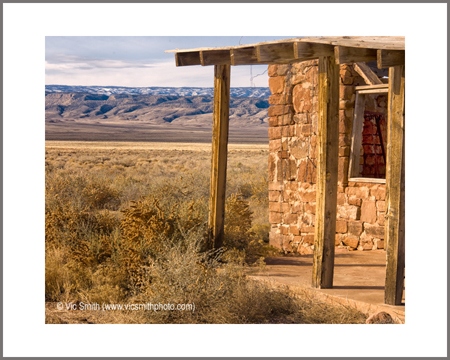

encamped, where Jacob Hamblin explored for a river crossing passage, where John D. Lee built his crossing passage and one of his homes, Lonely Dell, where the Spanish, Dominguez and Escalante, tried to cross on their search for a route from Santa Fe to California and where the Paria River allows access through the plateau for the earliest travelers. There are relics of these activities that can be seen from this starting point.

We can thank native peoples for the name Vermilion Cliffs. The southern Paiute were residents for 600 years before Europeans arrived. Their name was Un-kar Mu-kwan-Mu-kwan-I-kunt, meaning Vermilion Cliffs. Powell translated it and stuck it to the maps. “Paria” is also Paiute, and may mean water that tastes salty.

You can see and appreciate the Vermilion Cliffs from the highways, but to feel them you must get out and walk. I’ve done so, into Coyote Buttes, Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch and the lower Paria River. I’ve hiked to the bottom of the cliffs, felt their towering presence and seen the hardscrabble ranch buildings that still hang on to life. I’ve looked down and seen sand, everywhere. I’ve looked up and seen the clear bright skies. I’ve looked around and seen little water. I’ve put on the sunscreen and packed in the water. I’ll do it again.

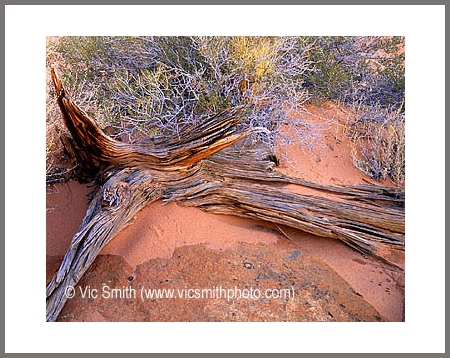

When you walk about, start by exploring the exit of the Paria from its canyon, walking past Lee’s Lonely Dell, smelling the fragrant sage, wading or hopping past goosenecks and through deep drifts of ancient sands. Then come back and climb the Spencer Trail to get a birds eye view of the river. If you are daring, find the Escalante Trail and follow it back to the Paria River, Lonely Dell, and your cooler of drinks.

Driving west along Highway 89A, look for the places you can get past fences get yourself up to the canyons, washes, promontories, piles , buttes and boulders that make up the southern edge. You are near the Old Spanish Trail that linked Santa Fe, New Mexico and Southern California.

Be sure to climb far enough to look down toward the Marble Platform (and toward the Kaibab Plateau, another story).

Drive as far as you can and hike the rest to the old Lee/Hamblin homestead, Bar Z, that used water from a spring at the base of the cliffs.

Turn north on House Rock Valley Road (a 4-wheel-drive road not passable if wet), a passageway between the Monument and the Kaibab Plateau. Stop at the Condor release viewing site, high on the cliffs, being used to restore California Condors to the Grand Canyon region.

Note the roads running to the east, up toward the plateau. Very sandy, use caution. You’ll also pass near an Ancestral Puebloan site, West Bench Pueblo, dating from about 1200 A.D.

Stop at the sweet spots, access points to the Coyote Buttes, showplace for sculpted sandstone, the Wave,

the White Pocket and the upper Buckskin Wash. You will need permits, sometimes difficult to obtain. Hiking can be hard and driving is a sandy challenge back there.

Continue north, then go east on Highway 89. Soon you’ll drop into the valley of the Paria River and the road to White House Trailhead. It will seem overrated given the volume of water, dense brownish greenish sludge that gives little visibility of the bed and likes to eat loose footwear, it carries. (This is the southwest where aridity can make modest water, or even the memory of it, grandiose.) Then again, sometimes it gets way more dramatic.

White House is where you start a journey into the Paria Canyon Wilderness, a forty mile four day trek, through the heart of the Monument to Lee’s Ferry, featuring narrow canyons, river-slogging with quick sand, rock art, arches, and more. (You can also “dive” the rockfalls of the Buckskin joining the canyon in the narrows. Much harder.)

Heading toward Page, you are looking at the north side of the plateau and the spectacular cliffs are absent. The climb to the top is longer but flatter and easier.

Continuing through Page and then south, there are glimpses of the Cliffs, the plateau and the broad portal of Paria Canyon’s channel to the Colorado River. Driving back to Lee’s Ferry completes the loop.

Now you have driven around these red walls, walked a bit and read the visitor center histories. Questions remain. Why are the cliffs here and how were they formed? The first answer is tied to pieces of the landscape that you’ve already seen, the Colorado River and the Echo Cliffs. This land was part of a broad basin that had many layers underlying the surface, some softer and sandy and others harder. At some point, the river started running down through it, using the elevation drop and its sediment to claw its way down, down, down. From above, storms brought water, snow, ice and rain to weaken, fill and split, to erode. The river sank, exposing new layers along its banks and the water ate into those layers. The softer layers near the top gave way, widening the canyon, and leaving piles of rubble at the bottom. Then the river sank into harder layers of limestone. The storms couldn’t penetrate the harder layers as quickly, so softer layers continued to recede and the platform was unveiled. The cliffs, Vermilion and Echo, and the platform, Marble, came into being and are still changing. Our earth is a restless place. The cliffs continue to move and the river continues down. The action is moving toward the northeast. If you come back in the future, say in tens of million of years, they will have receded further, may have disappeared, the canyon will likely be wider and the platform larger.

Why “vermilion”? Southwestern earth contains abundant iron, sulfur and manganese, gypsum, red, yellow, blue, white all of them defining colors in the cliffs. It is often barren of vegetation, so the soil colors are often visible. Hence the visible vibrant colors. These colors and their shades will change over time. Early morning and mid-day will give different sights. Wet cliffs will look different than dry ones. Stick around and you’ll see all the colors.

Why “Cliffs”? First answer: lots of time and dirt. The earth you see has been created in many different landscapes, oceans, rivers, lakes, dunes, and dunes. The land at the bottom of the cliffs formed under a western ocean landscape 350 million years ago, depositing hard limestone and leaving little sea creature shells embedded in those deposits. Much of the earth above the limestone came from high areas to the south and the east and was carried in large rivers. At times the land was wet and verdant. The top white layer, the dunes on the Navajo Sandstone formed when the landscape turned dry and when dinosaurs were in the middle of their 160 million year run. But the story doesn’t stop there. Remember the Grand Staircase? You are not at the top of it here. This earth continued to change, more landscapes were created, burying the earlier materials, filling them with more colors, pushing down, compressing, hardening. These upper layers are gone now, moved elsewhere by the forces of erosion. What is left is battle-hardened, slow to give and resolute.

Second answer: dry climate. The Colorado Plateau is an arid place, west of Powell’s Hundredth Meridian. Some climates are wet and erosion marches like an army. A dry climate turns erosion into a slow motion walk. Still relentless, it simply takes longer here. We’re lucky to have this window.

These sublime cliffs are ours to see, smell and feel. They don’t get the amount of traffic as their neighbors, Grand Canyon and the parks of southern Utah. So we can still have a quiet walk, a creatively challenging hike or even quietly tranquil contemplation. Please enjoy this place and these images.