This post and its collection started forming

some years ago. On our way to Montana one

summer we took a detour through

Yellowstone and then on to Bozeman.

It looked like an intriguing village,

so we dropped in and got coffee. Being me,

I quickly spotted a little grain tower and angled over to capture it in an image. After doing so,

I turned around and smack across the street was a cute old house, its porch lined with sunflowers

and it’s sidewalk lined with an old white picket fence. It was a treasured home with classic

boundary fences.

The image was shared at the time, but solely as a record of the trip. My work had been focused on finding displays of the earth’s vitality and majesty and capturing them for others to see. For the most part, humans and their artifacts had been unwelcome in my galleries. I was a landscaper photographer and human artifacts were at least a

distraction.

The next year we again headed north but drove through Idaho and the scenic Salmon River Canyon. It was a stormy day and just before we entered a slit in the dark magma, I glanced to the side and spotted an old abandoned jackleg fence, thrusting its nails to the sky in defiance of time and gravity. Perhaps I saw visions of a heroic past and perhaps simply saw the shape of the defiant log. I had a second image and the start of a collection.

As time has gone on, I’ve come to see that being in the wild is vital but not sufficient.

Lush valleys, mysterious canyons, rugged peaks and flowing water will always be

the most magical. But humans are a species among others and seeing the impact of

human dominance on our fragile world is also crucial, especially in an age where so many

are estranged from their earth. I’ve heard, “if you aren’t on the edge, then you are

in the way”. This post, and the images that support it, is me moving, baby steps,

toward an edge, the edge of seeing the game trails of humans. Some of this movement

is easy and some of it brings controversy. But photography has often inspired

challenges to what is commonly accepted.

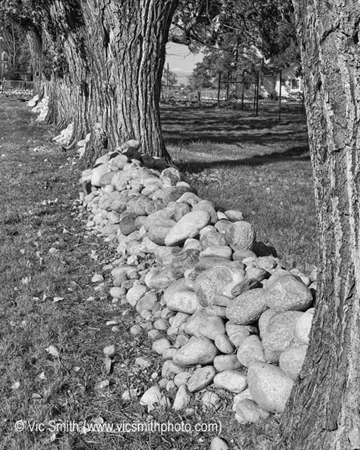

Fences, barriers, walls are ancient human artifacts creatively used to establish

boundaries. They seem to be a basic human response to the control of space. From time

immemorial, settlements worldwide have had walls both thick and thin and enclosures

of various kinds. The Romans filled England with field boundaries made from hedge rows,

in the south, or from stones, in the north and built Hadrian’s Wall near

the Scottish border in the second century.

Sometimes fences are accepted and other times they are questioned. Robert Frost wrote

about a wall in his poem Mending Wall. Every spring his stone wall needed repairs. He talked it over with his neighbor, with whom he shared the wall, asking him why a wall was required. There weren’t any animal combatants. His neighbor had pine trees while Frost

had apple trees. Neither was going to attack the other. But the neighbor would not go

behind his father’s saying: “Good fences make good neighbors”. Frost walked away,

thinking “something there is that doesn’t love a wall” and leaving the neighbor

to his mission.

I’ve noticed lots of fences along the way. Not all fences have been built alike.

They’ve been small, medium, and large. They’ve been rough and smooth and prickly. I

could sit on some. Some have still been vertical and others leaned. Some fences

have gone on forever without a break. Some have crossed impossible terrains.

Not all fences I’ve seen are used alike. Some have been for organization and some for

security. Some have been organic and some have been coldly efficient, maybe electric.

Most have stood alone, but some have leaned on something else. Some have been

ornamental or colorful. People have used some for announcements. Some have shown

the wealth and power of the owner. Some have warned. Some have guided. Some have

kept me out and others in. Sometimes there have been gates. Some fences are

publicly owned. Some fences have been left from a prior time, occasions for

our mysterious attraction to the old and the derelict.

Some fences are larger in scope but seem to fit into their space and others are

controversial, depending on your perspective. Consider the US/Mexico border fence, Great Wall of the Southwest. This metallic wall would plow through 2,000 miles of deserts as if they were soft putty completed. Along the way it will interrupt communities at all levels of existence. “Great Walls” have always required significant expenditure and seldom stood the test of time, especially in times of rapid change.

For those who may seek security in isolation, this structure provides comfort. For those

who may seek justice, it is an avoidance of the real issues and a dangerous waste of scarce resources.

The choice is ours to make.

And consider our big west, the land of big skies and open space. Vistas most often seem alive with textures and colors, “geographies of motion”(Ivan Doig). For those who came, and are still coming to America, open land was the symbol of freedom and opportunity, providing “elbow room for the spirit”(Ivan Doig). But today these vistas are often broken by lines of fence stretching to the horizon. Much of this land, 300 million acres (the size of three Californias), is public, managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the National Forest Service using grazing permits. Why are there so many fences there, where the deer and the antelope should be playing?

Over the last century one million miles of fence has been put in place on public land

to support livestock ranches, those rugged places of mythic proportions. Many folks

have deep family attachments to this lifestyle. Yet it is land

“beyond the hundredth meridian” (Wallace Stegner), with only sufficient precipitation

to support sparse groups of native animals and plants. Public land grazing in these areas

is a mismatch to it’s aridity, requiring strenuous effort to take over the native

resources and fight back the limitations and challenges imposed by the land. These

practices have often resulted in habitat degradation and isolation for the native life,

animals, plants, and water. According to the National Resources Conservation Service,

at least 50 percent of the desirable plant species have been eliminated on grazing

allotments, there is high erosion and weed invasion and riparian areas are damaged. Of

course, 300 million acres is a lot of country to cover in statements. There are bound to

be exceptions. But the most common situation is as described above.

Because of these challenges, nearly 90% of our beef now comes from east of the

hundredth meridian, not west of it. The state with the most cattle is Louisiana. Over half

of the permits to use public land are owned by wealthy absentee owners who produce few

cattle, using the land for aesthetic or tax reduction purposes. Far less than one percent

of the US population ranch on these public lands and over half of ranchers using public

land permits must rely on outside jobs to provide their living.

For those who prize historic ranching, these fences either don’t cause degradation or

the effects are acceptable. To them the fences bring order and a sense of continuity and

support an important lifestyle. For those who believe that the earth and its creatures

must be protected, the scope of fencing questionable, a threat to life and a subsidy

that we can’t afford anymore. And there are shades of gray in between the extremes.

Again, the choice is ours to make.

Fences bring order but they can also introduce complexity that changes over time. This

brings controversy that communities must resolve. It is hard work to achieve these

resolutions. But seeking consensus is the real key to lasting success in a complex world.

You’ll see a variety of fences and their contexts in this collection, gathered over several

years using multiple cameras. It is but a small sample of what I’ve seen

(there are plenty left for you). Keep your eyes open to watch for them.

(Thanks to Rob McKay Photography for the watcher)

I encourage your comments and critiques. If you wish to leave a comment, please

contact me and I will generate an account for you.

Well, I just read your post and love love loved it.

I spent many many hours as a youngster painting corral fencing on a ranch. Lately I have been removing fence out at my property near Flagstaff.

The acreage was double barbed wire fence with electric wire above it, then it had almost one acre fenced with a 6′ tall “elk” fence. I have removed almost all of it, leaving only corner posts for visual reminders of the property layout. I’m sure the prior owner would choke when they thought of the money they spent on fences and that I tore down. Why would anyone trash what so accurately & expensively defined their holdings?

Then there were the cages. The former owner planted trees and bushes that the elk love to nibble on. So they too were “fenced” in with silly mini cage fences. I never understood why they would plant something that needed cages. It wasn’t that once they were established you could take the cages off. Several trees have overgrown their circular cage and get topped by a hungry elk in drier times.

I see houses going up, people and more people moving in. I see almost all of them feeling the need to “define” their little square. Do they even think of the wildlife?

I have seen a coyote and a skunk climb right over a 6′ elk fence, and elk grazing inside the fence, too. It’s my opinion that if an animal can see what’s on the other side, they will get that meal, could be a garden, could be your pet. So much for money well spent.

I have really enjoyed those fences, especially when I am removing them and hope that others will see my example and follow suit. It really makes me feel I am giving something back to the critters. If an elk gets a belly full of lilac and the plant is never to return, so be it.

We choose to live out in the wilder part of Flagstaff, so why not embrace it?

Well, Those are my thoughts, thanks for for the good work , keep it up sir.

I recognize many of the fences in your fotos and loved the narrative! Thanks,