Visits to deserts have often been a part of my life. I was raised traveling to them, led by a father who could have been a “Desert Rat” but for needing to make a living. We traveled east out of Los Angeles, past the Whitewater River, into the open, high, solitary air, going to the Colorado desert or off to Saratoga Springs in Death Valley.

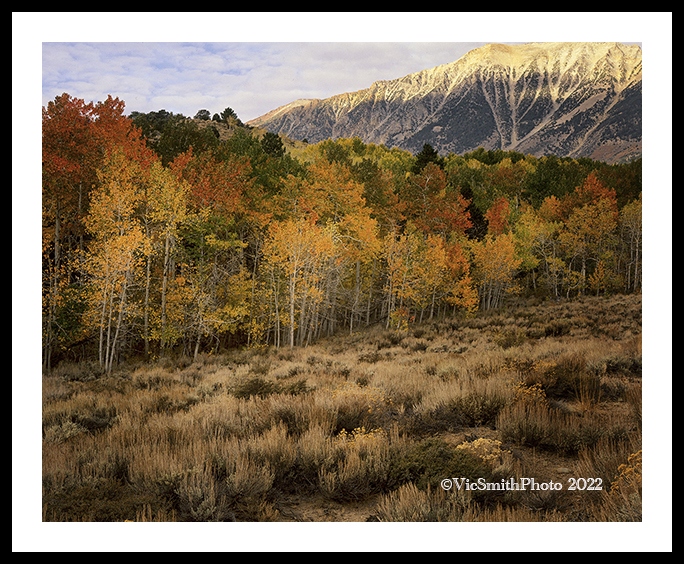

Then here I was, on another wide plain with sagebrush scrub at and then past me to the west, crashing into the base of white granite scarps that looked like they’d been popped up out a toaster.

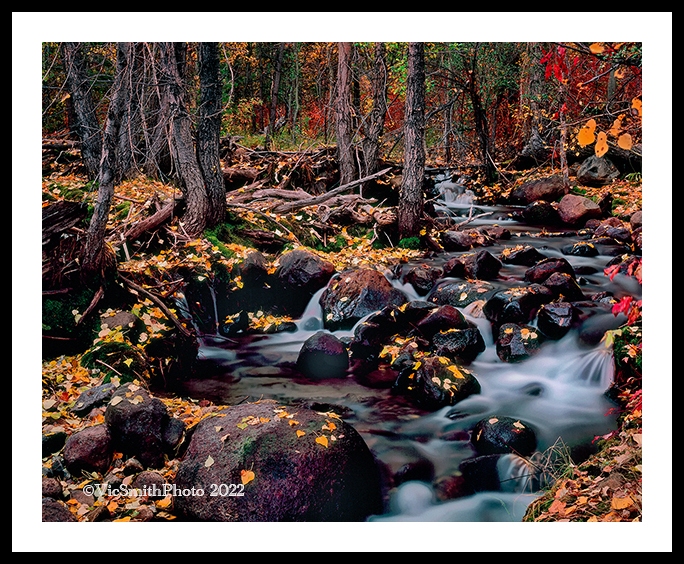

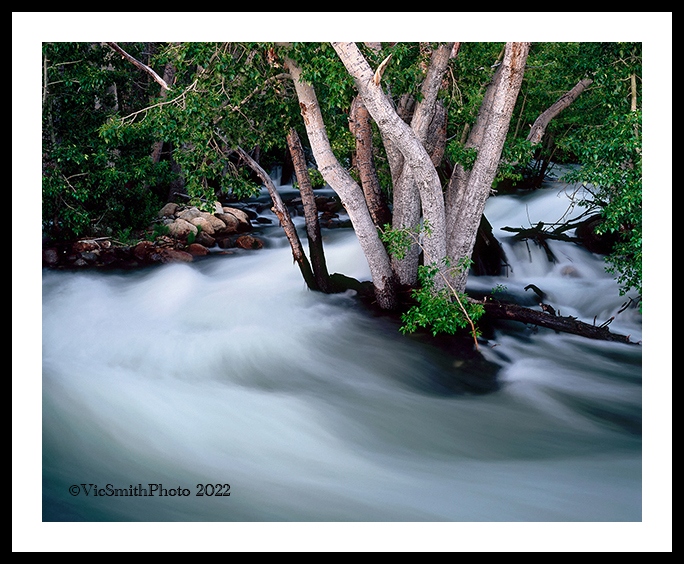

I was hearing a creek, rushing down to the east, past me, toward a lake alive with flocks of birds in continual motion, a lake in the sagebrush. The plain was the Great Basin Desert. The granite was the eastern crest of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

The creek was Lee Vining Creek. The lake was Mono Lake.

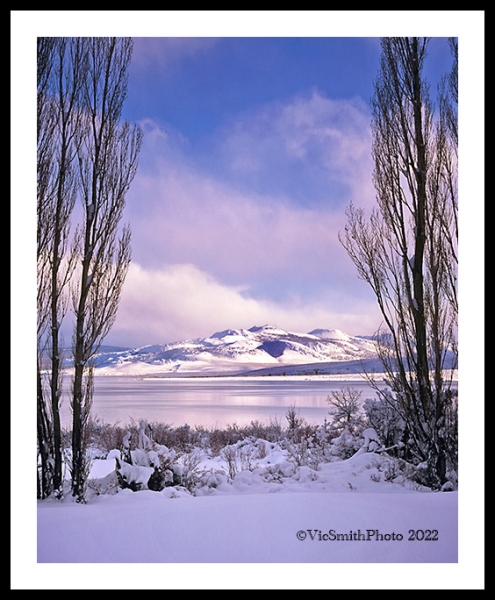

I was in the Mono Basin in eastern California, at the boundary of two earthly kingdoms, desert and mountain, each with an “immense breadth” (Robinson Jeffers).

This place became like home to me. I was recently single, had a good job (money and vacations), a love of the outdoors, a passion for photography, good equipment and good mentoring. It was a perfect storm of satisfaction.

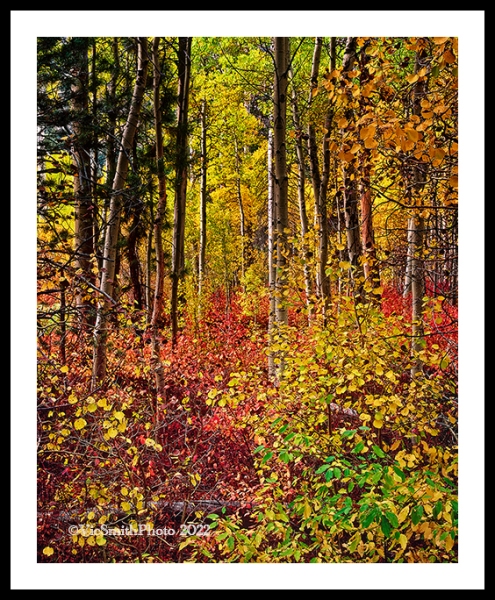

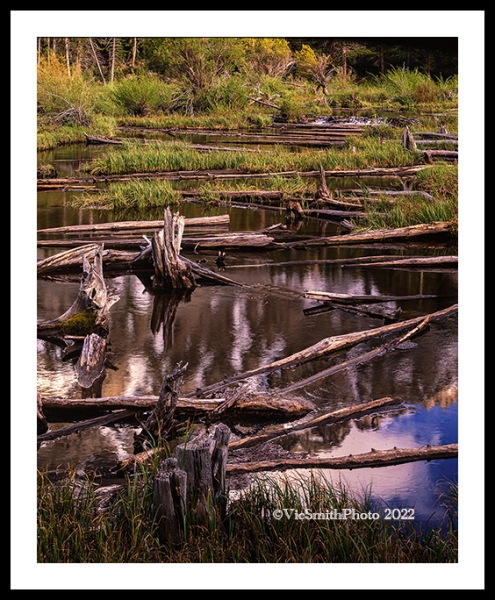

I got to see this land in all its finery, and all of its seasons. Its juxtaposition of high desert and Sierra scarps inflamed my vision of land. I hiked many trails starting at nearly 7,000 feet trailheads. I stood on the shoulder of 13,000 foot Mt Dana, gazing down on the ancient lake. I came to know many of its roads, meadows, bushes, trees, creeks, rocks, and resting places. I came to know folks who’d chosen to reside there. When I had to go home to live the rest of my life, I missed that land.

The images presented in this gallery are all of the Mono Basin. For a decade I marched to these scenes with a 30+ pound pack, praying for sweet light. The victories were captured on 4×5 film, BW or color transparency. Some were published in the MonoLake Committee calendar. They remain a standard against which I measure my work.

Deserts were a part of my young life. I was raised traveling to deserts, out of Los Angeles into the Mojave, past the Whitewater River, into the open, high, solitary air, going to Wiley’s Well and off to Saratoga Springs in Death Valley.

Then there I was, on a wide plain with abundant sagebrush scrub running west. This time the scrub was crashing into the base of white granite scarps that looked like they’d been popped up out of the plain.

I was hearing a creek, rushing down to the east, past me, toward a lake. The plain was the Great Basin Desert. The granite was the Sierra Crest.

The creek was Lee Vining Creek. The lake was Mono Lake, alive with its flocks of birds in continual motion.

I was in the Mono Basin in eastern California.

This place became like home to me. I was recently single, had a good job (money and vacations), a love of the outdoors, a passion for photography, good equipment and good mentoring. It would become a perfect storm of satisfaction.

It became a paean to movement and to life, powerful, beautiful, huge, serene. The vistas claimed me. I got to see it in all its finery, and all of its seasons. Its juxtaposition of high desert and Sierra scarps inflamed my vision of land. I hiked many trails starting at nearly 7,000 feet trailheads. I stood on the shoulder of 13,000 foot Mt Dana, gazing down on the ancient lake. I also came to know many of its roads, meadows, bushes, trees, creeks, rocks, and resting places. I came to know folks who’d chosen to reside there. When I had to go home to live the rest of my life, I missed that land. How did this all happen, this crashing of desert into some of the highest peaks in the continental US, the rising of the Range Of Light? A short break, then then on to seeking answers.

The images presented in this gallery are all of the Mono Basin. I would march to these scenes with a 30+ pound pack, praying for sweet light. The victories were captured on 4×5 film, BW or color transparency. Some would be published in the MonoLake Committee calendar. These images remain a standard against which I measure my work.

As I wandered the basin, my imagination ran wild. It became a paean to movement and to life, powerful, beautiful, huge, serene. The vistas claimed me. I was wonder-smitten (Maria Popov), finding eternity in the earth’s relentless impersonal processes. Simile and metaphor ruled as I sought images. The scarps became reminders of the eternal, like the towers of cathedrals. The Lake was an oasis. The Desert was a place of challenge, isolation and cleansing. Land was a spiritual force. That time was an escape to beauty that became like a bit of worship, with imagined chants and warmly colored windows.

But I was a scientist by in inclination, training, and profession. I asked, how did this all happen, this arid scrub, this crashing of desert into some of the highest snowy peaks in the continental US? This lake in the midst of it all?

Wonder wasn’t to be my whole story. It had to share space with a dance partner, my right brain. I wandered in the bookstore of the local Mono Lake Committee, seeing artwork and the work of scientists that had explored this earth. Walking between the worlds of imagination and study. The imagination came as it would when I was out in the field. The bookstore jump-started my study of the features I was seeing.

Was this crazy? I don’t think so. Haven’t you had similar sensations, seeing the earth as object, yet knowing that there is more, knowing the feel of eternity? Most people live between two worlds, between their imagination, their escapes, and their workaday worlds. At the time, mine just happened to be 600 miles apart from each other.

The granite walls seemed eternal, but they weren’t. The earth’s surface has a present, our current one, and a past, a very ancient one, deep time. Throughout this time it’s been a bit like a Manhattan street scene, with people moving randomly, bumping into, separating from, and lurching past each other. Its continents and islands are always moving, bumping, assembling, disassembling, sliding on.

This movement was a part of me. I was born an Angeleno, among great diversity, East LA and Beverly Hills, on the south side of the San Andreas Fault. I learned in my youth about land that shakes and jumps. My place lurched , unpredictably and relentlessly to the northwest, past land just 40 miles away that was moving at a slower rate and hence away. Walls would crack. Buildings would teeter. Cliffs would form, then crumble. I sought refuge under tables or in door frames.

California, and the entire pacific coast, is a bit dodgey like this. It is the product of a continual assembling, of collisions and discontinuities. “Exotic” continental pieces and island arcs, drifting across the seas along its western border, have crashed into it and become a part of its ever-widening girth. Like migrants today, the crashers brought their legacies with them, minerals including gold, volcanics, and rock strata.

The Sierra scarps are a result of this assemblage. 100 million years ago an arc came ashore and was pushed, under the continent, down about 60 miles (subducted) until it got down enough in the mantle to melt. Hot things rise. Up came the magma that would become the Sierra granite, large bubbles (batholiths) captured underground. This the first act of the Sierra drama.

80 million years later (less than 2% of the earth’s history) the second act unfolded. The lands east of today’s scarps stretched and thinned. Faults appeared and broke the earth into blocks that then tilted, down to the west, raising large chunks of earth, including the large batholiths of buried granite, down to the west, up on the east. The Sierra Nevada Mountains, with its steep Eastern crest, broke free, rose up and formed the scarps that filled my imagination. Mt. Gibbs was raised to nearly 13K feet (and it’s still going up), standing as a powerful reminder of the first act above the Mono Basin. (Mt. Whitney, 125 miles to the south, the tallest peak in the continental US, clocks in at just under 15K feet is also still rising, 1 mm/year.)

Then came the third act. The cold, wet Alaskan storms heading south along the Pacific coast ran into the new mountains. They captured the abundant moisture and sent much of it back down the sloping Sierra, back toward the Pacific Ocean. The eastern lands were largely starved. Beyond the Sierra block a large (190K sq mi, spanning parts of California, Nevada, and Utah) rain shadow (just 6 to 12 inches of moisture a year) was created , the Great Basin Desert.

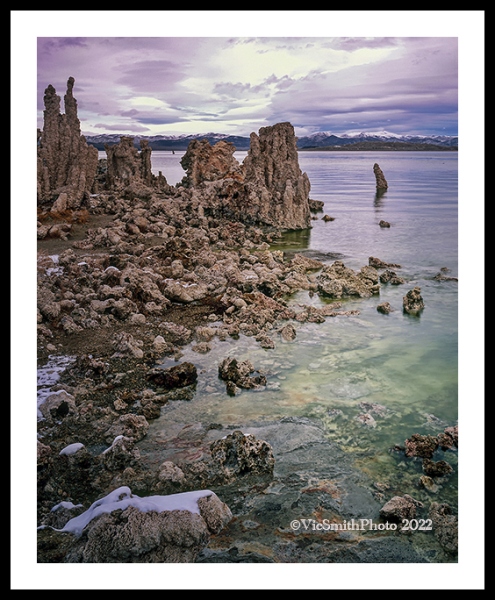

This desert, former ocean floor, received the water of the Sierra streams into lakes in landlocked basins. The land was salty. Water leaves the lakes only by evaporation. Mono Lake, one of the oldest lakes in the country, became concentrated, hyper saline (much higher than the Pacific Ocean) and alkaline.

The Sierra water was also underground. This water rose into the cold lake, forming tufa towers, landmarks of Mono Lake. The native calcium was precipitated out, into the towers. The towers come in all sizes. They are rough and tough, biting at boots during a traverse. Tripping could mean a serious trip to first aid. Still porous today, some still give water back. Time has toppled many tufa towers. At twilight they remain ghostly.

The epilogue to this history is that life on this new desert adapted. Plants and animals found ways to use the aridity and salinity to further life. The lake is full of brine shrimp and brine flies. Flocks of migratory birds, seagulls, grebes, ducks, geese, phalaropes, avocets, sandpipers, stilts, and the threatened plovers have fed on these riches.. Sagebrush and rabbitbrush have supported land animals. Mono Lake has been a vital garden for many, a key part of the pacific flyway.

And this garden has attracted people as well. The Kucadikadi people, northern Paiute, have resided in the basin for millennia, using the resources of the lake, the brine flies, and the minerals of the mountains. Going between their Mono homes and those of their cousins, the Ahwahnechee of Yosemite, to trade and celebrate. More recently, Americans also came, miners, seeking to extract the minerals upwelled from collided lands.

My dance found its high point, my moonwalk. Even though I don’t get there very often anymore, my imagination still remembers the awe that the land inspired and also appreciates the forces that created it. Two sides of the same coin. One reality.

There is a second epilogue. There’s saying in the west, “whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting.” The Mono Basin is awesome. But the Sierra water is also conflicted. Tufa towers are visible because water extraction has so lowered the level of the lake in order to send the water south to Los Angeles. See the story on the Mono Lake Committee website, www.monolake.org.