I was on the road, leading a tour group from Flagstaff to Winslow, a day trip, a journey back in time. We glimpsed an offramp leading to “Historic Route 66” and a long train carrying double-stacked containers. We dropped onto a broad brown grassy plain. Someone asked about another sign, to Buffalo Range Rd. I said that buffalo (bison) had once been prevalent, sometimes like a dense ground-cloud. Then they were nearly wiped out. To help preserve the species, the Range to the south was established.

Seeing their quizzical faces, I added that the hides, meat, and land of the bison became more important than the fading memories of them. The march of progress brought winners, like the train and this road, and losers, the bison.

Soon a dark brown cleft appeared on the horizon. Canyon Diablo snaked toward us across the brown plain and then whisked below us as we sailed over it on a large concrete bridge.

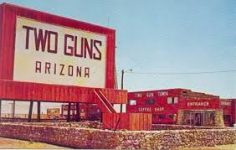

Fifteen seconds later, on the right, another offramp sign pointed to a spray of remnant buildings, “TG”. A weathered wall proclaimed “MOUNTAIN LIONS” and the skeleton of an abandoned gas station rose up.

My Images

Someone asked: Is that an old movie set? a ghost town?

I did my best to interpret, resolving to return.

Then I went back over the canyon, armed with background stories, questions, and a camera. I wanted to walk around TG, looking, touching, and listening, gathering impressions.

My boyhood memories arose as I entered. I was looking out the window of our gray station wagon after long hours sharing the backseat with my brother, hot, tired, cramped, finally getting to a stop, seeing an entrance to some attraction, getting out. I was joining others, eagerly climbing around coastal redwood titans or ghost town buildings, places of magic.

TG seemed abandoned. Remnants of structures were spread to my right and along a road going up to a ridge to the south. It was quiet except for engine noise from the highway.

I turned right on a meandering dirt road toward old rock buildings. I imagined hearing sounds of construction. The cool October breeze was warmed by imagined cars bouncing past me along the rocky dirt road that was lined by fences that had been cut open in places.

I went through a fence gap to the wall announcing “MOUNTAIN LIONS”. It was at least 10 feet tall, built of small rocks, the color and texture of those around where I stood, but rounded and flattened on the side facing me and stuck together with grout.

On the right side of the wall was an entrance into a passageway. I walked into the passageway, under large squared logs sitting on stone posts, and looked into a small room on the left, then went through to the back, and down a ramp to what appeared to have been enclosures, stone walls and chicken wire, cougar cages? Further below, I saw an old concrete bridge that crossed Canyon Diablo as it ran east.

I left the wall and looked for access to the bridge, passing a small building with a white plaster finish. The side that faced the interstate had a Route 66 symbol, with two guns, one on each side, curving toward the top of the symbol. Closer to the interstate was the outline of a foundation. Beyond that were two stone pillars, separated from it by about two car-widths, standing near the interstate boundary fence.

I crossed the bridge, passing red stone walls that looked like the shell of a former building. Beyond this and through another fence gap were long rock walls that defined rooms lining the edge of Canyon Diablo. To its east stood a four-hole outhouse. In front of the rooms was a tall round stone building with a circular staircase going to a second story. A concrete slab with large bent bolts and rusted-on nuts, looking like a gas pump island, lay in front of this round building. As I returned to the bridge, I noticed, across the canyon from the red stone building, several more buildings, one of which was above a cleft in the canyon wall.

I went up the hill past the gas station skeleton, past an empty wooden building, past an old planter with a sign faintly noting Route 66 and Two Guns, past large tanks, to a pointed-roofed building, leaning to the left, with “KAMP” painted on each side. Contrails rushed over in the big blue sky. Next to it was a pool with a cabana on the far side. Beyond the building, RV-park utility boxes were arrayed out to another empty building.

All the remnants along the road were graffiti-laden. The cabana and the pool seemed like a crescendo, rhythmically wild with bright colors, carefully placed edges and signatures.

Overlooking the lower area from the pool decking, I could see what seemed like waves of time that had passed through TG. There was an old, substantial bridge, still functional but now not really used, its road heading across the plain to the west. There old roofless buildings and what looked like a former gas station along the bridge road. There was a cleft in the canyon wall, into which were walkways. There were Route 66 signs facing the interstate. There was a place to “Kamp”.

Clearly the story of Route 66 was part of the story of TG, but it seemed like there was more. I went back to the bridge and looked at the empty buildings and then looked downstream into the canyon. What was beyond the interstate bridge we’d crossed? Its ledgy depths seemed dark and mysterious, a place for chanting. I saw willows and a narrow water course with standing pools left over from former flows, their surfaces rippling in the breeze. Water is life, so I started listening for stories I’d heard to emerge and lead me into its chasm.

Those stories are long, started by ice age water flows that carved into the underlying 250 million year old limestone, creating a passageway. The Zuni people tell us that a long time ago they passed through this passageway. They had emerged into this world in the GC and then migrated, always aiming at the center place of their world at Zuni, NM, up the Colorado River, then up the LCR, then up CD. They collected sacred materials in Canyon Diablo, materials that became part of their ritual stories. They also tell us that Zunis still return to Canyon Diablo to replenish those materials. To the Zuni, Canyon Diablo is a land of mystery, the land of their gods.

Other pueblan folks have also given us stories of migrations. They farmed the canyon floor near TG, leaving pottery shards that date back a thousand years. Like it did for the Zuni, Canyon Diablo gave them passage, sustenance, refuge.

What about the name, Diablo? Stories of mystery and witchcraft were a part of the native cultures when the Spanish passed through in the sixteenth century. From those stories and the legacy of their own European witchcraft stories, the name Cañon Diablo arose.

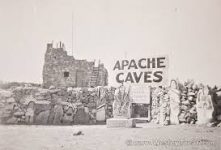

Apache and Navajo also have stories of the canyon. Caves in the limestone walls have been places of refuge for them during times of trouble, like when Indian Agents kidnapped children for Indian Schools. In addition, the east rim has been a travel route, for trade to the south and for warfare. Apache came north to attack Navajo villages, stealing, killing, kidnapping. Navajo chased after them.

These conflicts would provide a gift to TG, a cave with a tragic story about a final conflict. After one attack, a group of 42 Apache hurried south and took refuge in a cleft in the canyon wall, the one by the bridge in TG. The Navajo found and killed them. The Apache then put a curse on that cave, judged it to be haunted, leaving a mystery that would become part of TG lore.

So imagine being someone walking in the mysterious silence of the canyon bottom, the land of your people’s passage, collecting plants 165 years ago. You hear the clank of a pick on rock and see a spray of broken limestone coming down at you. You might wonder: are the spirits angry?

The falling limestone meant that CD had changed hands. Creator had given it to native peoples, to care for. Americans had taken it, for extraction. They saw it as an obstacle to their westward progress, a place to be conquered, rock by rock.

The clanking had been directed by Whipple, a surveyor mapping a railroad path between the Mississippi River and Los Angeles, following the 35th parallel. He got there in 1853 and found a chasm 146 feet wide and 255 feet deep with rock good enough for bridge supports. He put “Canyon Diablo” on his map, and went around the obstacle to the north.

Soon there was a wagon road following the survey route. And then, thirty years later, the railroad arrived, laying track along Whipple’s route for their 400K lb engines. They got to the rim, stopped, measured the width and depth of the canyon, ordered a bridge (that was too short; the devil hissed), ordered the right one, and began building bridge footings.

They needed workers to build the bridge and a transfer depot, and to haul freight and passengers from the depot around the chasm during bridge construction. In 1880 ramshackle housing and a town named after the canyon erupted just to the east.

Canyon Diablo grew to be 2000 people. There were bridge builders, carpenters, teamsters, Civil War veterans, immigrants, freed slaves, and a school teacher. There were merchants, Ching Wong, a beef stew peddler and Herman Wolf, an indian trader.

There were also the normal scoundrels of western folklore: gamblers, thieves, bar owners like “Keno Harry”, brothel madams like “Clabberfoot Annie” and “BS Mary”, each famous for publicly yelling and shooting at each other across the main street.

All these people shared Hell Street, a place lined by wooden buildings that housed 14 bars, 10 gambling dens, 4 houses of prostitution, and a few shops. Murder and robbery were common, in town and on the bypass road.

Where was “The Law”? A sheriff was sent in. He lasted from 3 pm to 8 pm. The next one lived 2 weeks. “Bill Duckin” lived 30 days.

“Fighting Joe” Fowler left after 2 weeks. More came and left until the town dried up.

Diablo climbed the canyon wall and danced in the town for 21 years, until 1903, when the bridge was completed and the railroad bypassed the town.

Hell Street sank back down. Progress moved south just 3 miles.

Build the railroad and they’ll come. People did, to live, work, and travel. By 1914 Americans had half a million cars. They wanted to get places with those vehicles, on roads that were predictable, fast, and hospitable.

By 1907 northern Arizona business leaders had seen the future and hacked a new roadacross the plain between Flagstaff and Winslow, avoiding the long diversion around the northernend of CD. Their road became known as the Old Trails Highway. At a Canyon Diablo crossing three milessouth of today’s TG, ramps were hacked into the canyon walls. The Oldfields built a house witha trading post. This road was quicker and friendlier, but during spring runoff or flash floods travelers could find the canyon passage difficult.

In 1914 the Flagstaff/Winslow highway was shortened by rerouting it south from the northern end of Canyon Diablo to what is now TG. A reinforced arch bridge, the one that I had crossed, was built over Canyon Diablo. This new path became part of the National Old Trails Highway and the people who would become part of Two Guns lore began arriving.

In 1922 Earl and Louise Cundiff, immigrants from Arkansas, bought 320 acres of land on either side of the new bridge. They built a general store (the red-walled remnant) and a campground just to the west of the bridge. They named their refuge Canyon Lodge. It got a postmark in 1924.

In 1925, several more characters arrived.

The Cundiffs leased land to Harry Miller, “Two Guns” after his friend William S. Hart.

Miller came from the trading post in Walnut Canyon to the west. The Millers built the Two Guns Zoo, the set of rooms beyond the bridge along the canyon rim. It had mountain lions, a bobcat, a badger, a gila monster, goats, and much more.

He also explored the Apache Death Cave, using the the curse, developing a trail and opening the cave to the public. Miller was the first to use highway signs to attract travelers to his bankable mysteries, his zoo and cave

Miller leased land to “Chief” Joe Secakuku, a Hopi Snake Society chief and veteran of Fred Harvey attractions

.

He performed native dances, ran a restaurant, a curio shop. He built the square stone building above the Apache Death Cave as an entrance station for cave tours.

“Rimmy Jim” Giddings arrived from Flagstaff.

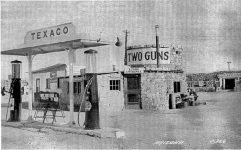

He built a Texaco gas station and curio shop in front of the Zoo the round two-story building .

I can imagine seeing Miller’s signs, getting to the Zoo, finding fuel for our car and my people, watching a Hopi dance, and then walking into the cool cave, after a long, dry drive. What an itinerary!

By 1926 Canyon Lodge got into the big tent. Its highway joined the growing Route 66. But the devil was hissing, even amidst the joy. Miller had a disagreement with Earl Cundiff and shot him with each of his two guns. He was acquitted, self defense. “Canyon Lodge” became known as “Two Guns”. The Cundiff store burned. Miller tried to take away the Cundiff claim. Sabotage broke out. Miller was mauled by a cougar and bitten by a Gila Monster.

By 1930 the characters and the highway were moving on. Miller left for the Painted Desert. The Chief left for a trading post in Holbrook. Rimmy Jim left for Meteor Station.

In 1937, Route 66 moved a bit north, to a new bridge. A new Two Guns Zoo, including the current Mountain Lion wall, was built by Louise Cundiff and her new husband. A new red Rimmy Jimmy gas station, the one with the posts, was built. In 1947 the road moved again, to the present interstate path.

In 1950, 28 years after it had arisen, the fire in Two Guns dimmed. The Zoo was closed. The property was sold to S.I Richardson of Gallup, NM.

In 1963 Benjamin Dreher opened Two Gun Town. He worked on restoration, opened another campground, and gave tours. In 1967 Interstate 40 replaced Route 66 at Two Guns. In 1971 the gasoline tanks at Rimmy’s exploded. Two Guns was swept by fire. The interstate had to be closed. Dreher left and Two Guns was bypassed.

In the mid 70’s a Shell gas station, the skeleton, and the KOA Kamp, opened just for a decade.

In 2011, Russell Crowe was rumored to have bought Two Guns for a movie re-make. Nothing happened.

There is a real estate listing available, 231 acres for $3M, an appreciation of 21,000% from 1922. More progress for the Tombstone of Route 66?

But wait.

There is public evidence of the drama of Two Guns. But did the Canyon Diablo hellscape really happen?

There is no official record of the Canyon Diablo sheriff problem or of Hell Street. Indeed, the railroad bridge workers lived on the other side of the canyon, in stone buildings in a shallow side canyon under the shadow of the looming bridge for just two years. Those stone buildings are still evident, at the end of another dirt road.

The telling of the Canyon Diablo story, Two Guns, Arizona, emerged from a local guy, Gladwell “Toney” Richardson, prone to tall tales, the author of over 300 western novels. He came from a prominent Gallup trading family who eventually purchased Two Guns. Gladwell ran it.

Did he create the Canyon Diablo story out of his western novel impulses and his desire to have a romantic mythology for this part of Route 66?

Sorry.

CD and TG were both born into that most American impulse: progress is to the west. Canyon Diablo now lives in the shadows, barely visible. TG lives on an interstate highway replete with reminders of its Route 66 heritage, glimpses clearly teasing us.

Like the Zuni, puebloan peoples of the southwest have been a people of migration. When they left places they did not abandon them. They left spirits and “footprints”, not “ruins”. Descendants return to the “footprints” to commune with remembered spirits.

CD and TG had people who chased promises of fortune and freedom as progress arrived and then moved on. The western promise dreams of Route 66 and the wild-west six-shooter allure of Canyon Diablo still attract the curious. Now bypassed, both towns live on in imagination because they give off a somnambulant vitality, remembered or imagined. Is the TG graffiti the work of spirits? Of the town or canyon? People promoting tourism call them “ghost towns”, places of spirits, our “footprints”.

My grandparents migrated west, one from the midwest to the northwest and the other from Sweden to California. My parents followed them, following the open road with the roadside attractions and ghostly remnants, hitching rides with progress and enjoying the opportunities.

Is the Canyon Diablo haunted? Is it just a canyon? It and its offspring are surely haunting.

I am someone who remembers car rides and escapes into magic. I keep those memories on my bookshelves and glance at them as I walk through the world around me.

[A postscript: Two Guns and Canyon Diablo are public places, full of stories that twist and turn, like the canyon they hug. Books, especially on Route 66, are legion (the one by Thomas Arthur Repp is excellent). Online searches bring a barrage of those stories, of all kinds, including the colorful history by Gladwell Richardson, and every kind of road journal imaginable. So of them are true and others are mistaken, stories circulated around the circle. I’ve tried to travel between them, picking the best fruit. I am telling a story, not just a history.]

**this piece is excerpted from a longer work intended for publication submittal

**please contact me (vic at vicsmithphoto.com) if you are interested in reviewing it

My thanks to Jessie, Rich, Sean for their help

V2 190210