“Bitterroot” is a strange name for a place. Yet that is the name given to a beautiful valley in western Montana. The Bitterroot is a plant, now the state flower of Montana, grown on drier mountain slopes. It was well known as a delicacy and medicine to the Salish, the native inhabitants of the valley for a thousand years, before Americans arrived 150 years ago.

Today I’m standing on the bank of the gentle Bitterroot River, with its Class I rapids, which flows through the middle of the valley for 50 miles on its journey to join the Clark Fork River in Missoula. I see the sky in the water’s surface and through the clear water I see the bottom rocks.

In front of me, to the west, above the cottonwoods and conifers, are the steep eastern faces of the Central Bitterroot Mountains, a part of the Bitterroot Range, notched by gray canyons over a thousand feet deep with spires along the edges. Their highest point, Trapper Peak, sits 6,000 ft above the valley floor. Behind me are the Sapphires, rounded mounds piled high. The Bitterroot range is the western edge of the Rocky Mountains and the valley is the longest valley in the that range.

From afar the Mountains look old and hard. Hard they are, having formed down deep under conditions of heat and pressure. But old they are not. Indeed, they are young by earth standards. They formed below the surface about when dinosaurs disappeared (11:41 pm on a 24 hour earth history clock). As they formed, they rose, sloughing off their crust and sliding it east to form the Sapphires. Glaciers completed the look, carving mountain valleys and the valley of the Bitterroot.

The sky that rises above the crisp mountain edges is big, whether it is blue or the white, gray and black of clouds. The mountains can collect over 500 inches of snow each year from the sky and the clouds, filling streams, creeks, ponds and eventually the river. Water is seldom far away in this land, in distance or in depth.

Looking up or down the river, I see land that humans have divided among themselves, but in fact birds and other wildlife share custody. Geese, ducks, osprey and many other critters are seen and heard along, by and over it.

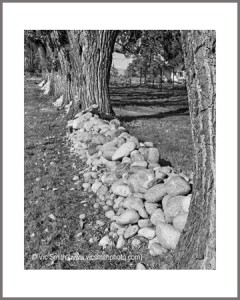

Looking around the land of the Bitterroot, I see fields and the fences that bound them. The weather of the Bitterroot, mild by Montana standards, and transportation costs have limited the growth of commercial crops, while private gardens abound. Some apples are grown, but mostly the bounded fields house livestock or are used to produce feed grains for the livestock. These fields are often shared with deer and sometimes with elk.

It is a land of short history but long memories. People of the valley can and often do trace their history back multiple generations. Their predecessors came to this place, claimed space for themselves and started a new life based on hard work and creativity. They hunted, fished and grew what they could. Their attachment to the land and their ways is deep and often cautious of those who come from other places, but gracious to those who earn their trust.

I trust that these words and the linked images will tell a good story about this wonderful place.

All Images & Stories Are ©VicSmithPhoto